By Vincent Dorrington

On a winter’s night in 1852, death came quickly and without warning to many people in the Holme Valley as they slept in their beds.

The devastating flood that swept 81 men, women and children to their deaths was reported in the national newspapers and widely read about by a shocked Victorian public.

Holmfirth was a mill town of nearly 2,500 people at the industrial hub of the textile industry. However, by the 1830s it had a major problem. It did not have enough water to provide a constant supply to the mill ponds and the water wheels of the Holme Valley.

Between 1839 and 1842, Bilberry Reservoir was built at a cost of over £9,000 to solve this problem. The dam wall was over 300ft across and 67ft high. People regarded it as an engineering feat and a marvel to behold.

It rained relentlessly for two or three weeks before the dam burst. Locals heard rumours of water lapping over the embankment wall and feared that the dam would not hold.

On the evening of February 4 1852, some came to see for themselves, standing on a nearby hill in the moonlight. They watched in horror as desperate families, on the other side of the dam wall, tried to save their furniture before the dam burst.

Then an hour after midnight on the night of Thursday February 5 1852 the dam wall gave way – a catastrophe was about to happen.

There was a huge roar, an immense sheet of mist rose up. Witnesses reported how a rumbling sound like thunder rolled down the valley.

The air was full of shouting and screaming as 86 million gallons of water rushed towards Holmfirth. The deluge took under 15 minutes to reach the mill town.

The destruction and loss of life was unprecedented. 81 people lost their lives, 45 of them were children or teenagers.

Over 7,000 workers were put out of work as many mills were destroyed. Queen Victoria was so shocked that she helped to establish an appeal fund for the destitute and unemployed victims of the flood.

Widespread public sympathy for the victims raised nearly £70,000 (equivalent to about £14 million today).

Bodies were taken to nearby public houses, some were found as far away as Wakefield. The young skeleton of a girl – probably Sarah Woodcock – was the last victim to be recovered – found in a Holmfirth mill pond channel being cleared – in 1990.

The path of destruction horrified local people. In places there were 3ft of rubble when the water subsided. Most of the water swept away the water wheels and steam engines of the mills that laid in its path.

Bridges were swept away at Holmbridge and in Holmfirth. Such was the power of the water, Digley Mill’s boiler of 10 tonnes was found at Hinchliffe Mill. Miraculously the mill’s chimney remained intact and upright. It proved to be a major tourist attraction after the flood.

Perhaps St David’s Church at Holmbridge presented the most bizarre site. Water rose to 5ft inside the church. In the middle of the aisle, a dead goat was found with a floating coffin. Factory machines and cloth were all over the graveyard. Victims of the flood were buried in that same graveyard.

Coffins were also washed away from the vault and graveyard in Holmfirth’s Wesleyan Chapel. One of the coffins belonged to John Harpin. He had been one of the main promoters for the building of Bilberry Reservoir.

Many a story was related by local people of their lucky escapes. Houses collapsed just after people got out.

A local man named Peter Webster watched on in horror, as his wife and children fled their cottage with clothes on their backs and hastily grabbed bread and cheese – just before the flood washed away their home.

A Mr Crompton barely had time to put his trousers on and escape before the waters struck. Some like the Ashall family tried to dress before escaping – but Victorian modesty cost them their lives.

Other survivors hung onto wooden beams, like Mr James Mettrick of Hinchliffe Mill and lived – though his father did not.

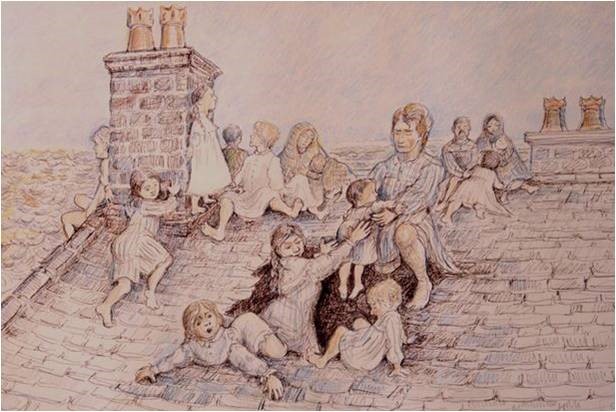

At Harpin’s Mill, five workers hung onto the mill’s rafters to escape death. Many householders escaped the rising waters by knocking holes in their ceilings and roofs. Some climbed up chimneys to reach a higher level.

Other fortunate people had very lucky escapes. A wealthy widow, the resolute Mrs Hirst, had been made aware of the dangers but sat in her cellar reading the Book of Job with her youngest son wrapped in a table cloth nearby.

Neighbours saved her just in time, though she had lost £50 in gold and silver. Her Bible and glasses were found in the mud. Later Mrs Hirst’s granddaughter donated the Bible, with the rusted imprint of her glasses, to St David’s Church.

Some people who also had warnings were not so lucky. Wealthy mill owner, Jonathan Sandford, had over £3,000 in his house – possibly to buy stock in the London and North Western Railway – decided to stay. Later his body was found with that of his two young daughters and his house-keeper.

The greatest loss of life (36 people) happened at Hinchliffe Mill where the river flowed in a curve, sweeping away houses on its bank.

One of the most tragic stories is linked to the disaster took place there. Two children of the Charlesworth family, on Water Street, escaped to a neighbour’s house but ran back to save their two hens and were drowned.

READ MORE: Read more of Vincent Dorrington’s historical features HERE

The death of Mrs Hartley and her children in Holmfirth is one of the most alarming. She heard of the dam wall dangers but ignored them and felt she was safe. Mrs Hartley put her eight children to bed. She herself went to bed at one o’clock in the morning.

Tragically, she drowned with five of her children. She was last seen trying to save her two-year-old daughter, but both were carried off.

Mrs Hartley’s last words were to say goodbye to her son David. He watched from a roof as his mother and her baby were swept away in the waters.

Ian Harlow’s book ‘The Story of the Floods in Holmfirth’ provides a graphic and full account of the trauma people experienced on that terrible night.

Contemporary images from ‘The Illustrated London News’ are equally graphic. They brought home to Victorian England the scale of this disaster and helped the public appeal fund. It also encouraged spectators to see the Holme Valley’s destruction for themselves.

A public Inquiry was held at ‘The White Hart Inn,’ barely two weeks after the disaster. It unearthed some disturbing facts.

George Leather, the reservoir’s engineer and famous for building the Leeds Bridge, said its plans were rushed through by the Commissioners.

He had advised that the first contractors should not be used but was ignored. It emerged that Leather rarely visited the site during the first two years of construction, when the foundations were being built.

By 1845 he pulled out of any involvement with the construction of Bilberry Reservoir and claimed the maintenance of the reservoir was not part of his duties.

John Towlerton Leather, was the nephew of George Leather, and had helped his uncle in the capacity of engineer.

In 1864, John Towlerton had worked on the Dale Dyke Dam in Sheffield as chief engineer. Like Bilberry Reservoir, Dale Dyke Reservoir had a stone and earth embankment with a ‘puddle’ interior wall.

Once again the embankment collapsed leading to the deaths of over 240 people. Building such dams was at the cutting edge of Victorian technology. Clearly lessons had not been learned from the Holmfirth disaster!

Workers told the inquiry that a stream was found at the foundation and no attempt was made to channel it away from the earth and stone embankment with a ‘puddle’ core running through its middle.

This core compromised of a clay and gravel ‘puddle’, at the centre of the dam wall, which was supposed to make the wall water-tight and prevent leakage. The central ‘puddle’ core of the embankment also became soft, rather than solidly strong.

The embankment settled towards its centre which added to its problems. Significantly the bye-wash was above the level of the central dam wall – it was of no use in easing the pressure on it.

The overflow system also had one of its shuttle doors blocked. Water could not be released to ease the pressure on the dam wall. In short, an accident was waiting to happen.

Finally, the inquiry concluded that the reservoir was defective in its construction and that the ‘commissioners’, ‘chief engineer’ and ‘overlooker of the works’, were all greatly culpable.

It was clear this was a man-made disaster. A verdict of manslaughter could not be brought in because the Water Commissioners were a Corporation and not a private firm. Technically they were answerable only to Parliament.

However, public criticisms by Captain Moody (the Government inspector) of the Water Commissioners was greeted with public applause. These people wanted justice as well as answers.

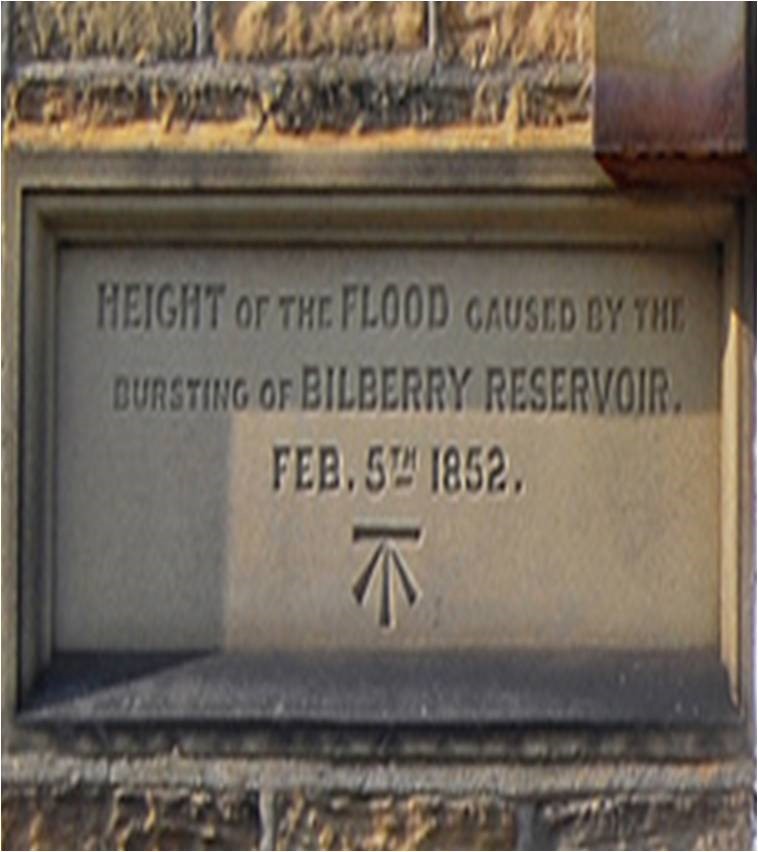

Today, Towngate in Holmfirth, has many plaques to commemorate the Great Flood. The height of the waters can be seen on markers which act as a grim reminder of the terror people faced that dark winter’s night in 1852.

The loss of so many lives has cast a long shadow in Holmfirth.