By Vincent Dorrington

In 1862 the greatest known long-distance runner in the world came to Lindley Moor as part of a touring show.

Thousands flocked to see Louis Bennett, better known as ‘Deerfoot’, the famous Native American athlete who had already beaten the champion runners of England.

Deerfoot was in effect the first great star of running or ‘pedestrianism’ as it was known then.

Running races had begun as pedestrianism (fast walking) from the late 1700s. The wealthy aristocracy challenged each other’s coachmen to race each other. Throughout the first part of the 1800s this evolved into trotting and then running races, often at fairs and markets.

Huge crowds came to bet on their local favourite. Running races throughout Britain were covered by their local press and in national journals like ‘The Sporting Life’ and ‘Bell’s Life.’

The names and sporting feats of competitors became widely known as they represented their town and region.

Names like: John Brighton (the Norfolk milk boy), William the American Deer Jackson, Jack White the Gateshead Clipper and, above all, Teddy Mills, better known as Young England.

In effect they were all professional runners with managers. They competed for prize money, cups and belts and a share of gate money. Wherever they raced there was gambling, the threat of violence but, above all, excitement.

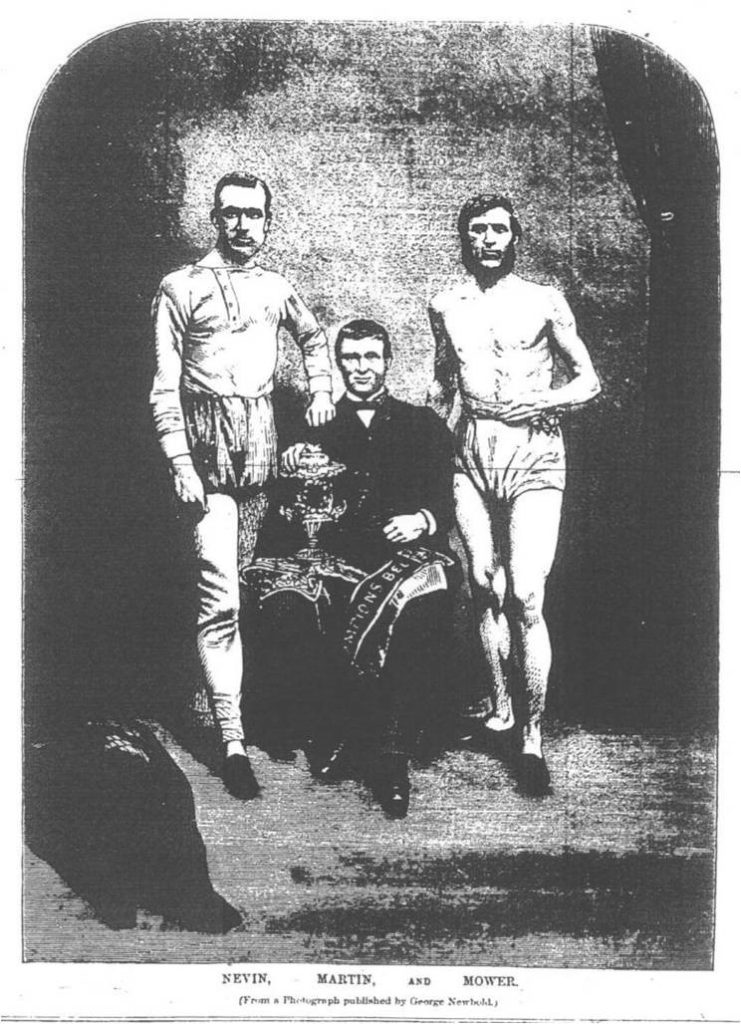

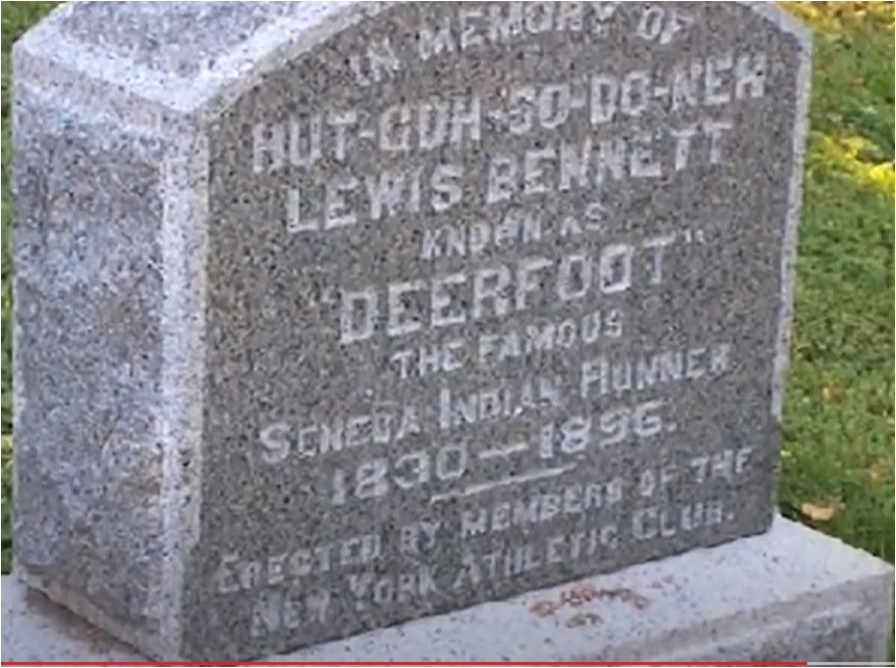

It was into this world that Lewis Bennett (Deerfoot) emerged. In many respects, he was the creation of his manager George Martin.

In the late 1850s, Martin took a team of the finest British runners to America and it was here that he came to know Bennett.

As a young man Bennett acted as a runner for his Seneca tribe in Buffalo, upstate New York. Some said he was called Deerfoot because he could run faster than a deer.

The truth is hard to establish but he could certainly outrun horses at county fairs and was a match for Indian champions.

Meeting Bennett was seen by George Martin, a former runner himself, as a great way to make money. He would bring Lewis Bennett to England on Brunel’s Great Eastern steamship.

Martin’s plan was to promote Bennett as a running sensation, the likes of which had never been seen before.

He would be promoted as Deerfoot to capture the British imagination. Then he would take on all challengers and, with the help of the press, would become a celebrity, a sensation, the talk of the town.

This certainly worked. The name Deerfoot became a part of popular culture. People spoke of ‘doing a Deerfoot’ or being as ‘fit as Deerfoot’ and medicinal cures often claimed the backing of Deerfoot.

The Royal Olympic Theatre in London performed a play about his life and a popular song was written and widely sung. Perhaps the most prestigious of Deerfoot’s races was when he ran in front of Prince Albert Edward (the future King Edward VII) at Cambridge.

For most of early 1862 there was a long list of champion challengers defeated by the great Indian runner. Races varied from three, four and six miles to 10, 11 and 12 miles. Deerfoot was at his best over the longer distances – the record books bore witness to his supremacy.

George Martin wanted to promote his running star even more, so from May 1862 a nationwide tour was undertaken, especially to the industrial towns of the Midlands and the North.

Publicity stunts were staged to keep Deerfoot’s name in the papers – possibly the most infamous was when he pretended to scalp someone with a tomahawk in a Worcester inn.

It seemed wherever the written word was printed in England in 1861 and 1862, Deerfoot’s name would be found.

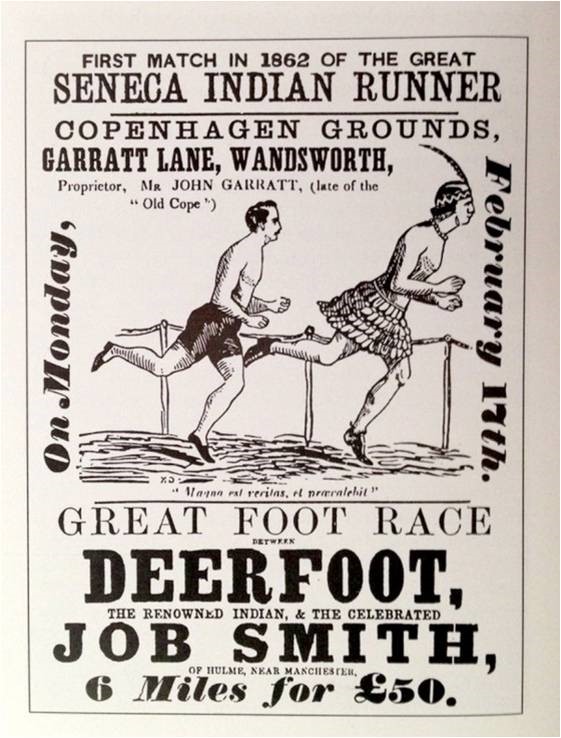

Martin knew that image was all important as he started to create the star Deerfoot out of Louis Bennett. All adverts used the sole name Deerfoot – a marketing brand ploy.

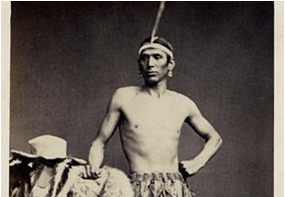

Photographs emphasised the Native American heritage of Lewis Bennett. He was strikingly Native American in appearance, with bronzed skin, black hair, eagle-beak nose and piercing eyes.

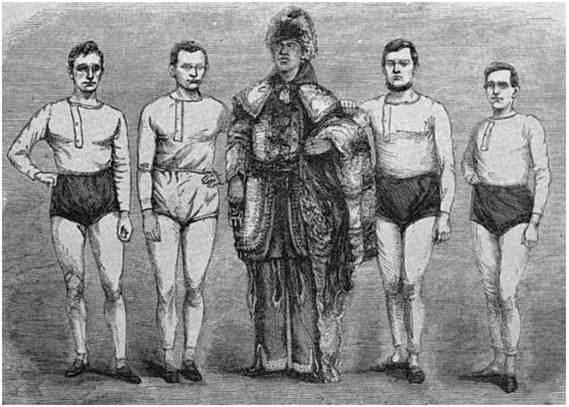

Deerfoot dressed in a Native Indian wolf skin cape blanket for show. When racing he wore an eagle feather on his headband, a modified skirt cloth ornamented with porcupine quills, beads and jingling bells and moccasins on his feet.

Rarely, did Deerfoot wear the modest linen racing attire of the time (long drawers and a woollen shirt). Instead he ran bare-chested in his native attire.

This scandalised the Victorian public, many had never seen anything like this before. However, reporters noted that the sex appeal of Deerfoot attracted many female admirers.

Standing at nearly 6ft and weighing in at a muscular 13 stone, the Native American was certainly a sight to behold.

By the time that Deerfoot came to Lindley Moor in April 1862 he was part of a travelling show and had beaten nearly all challengers before him.

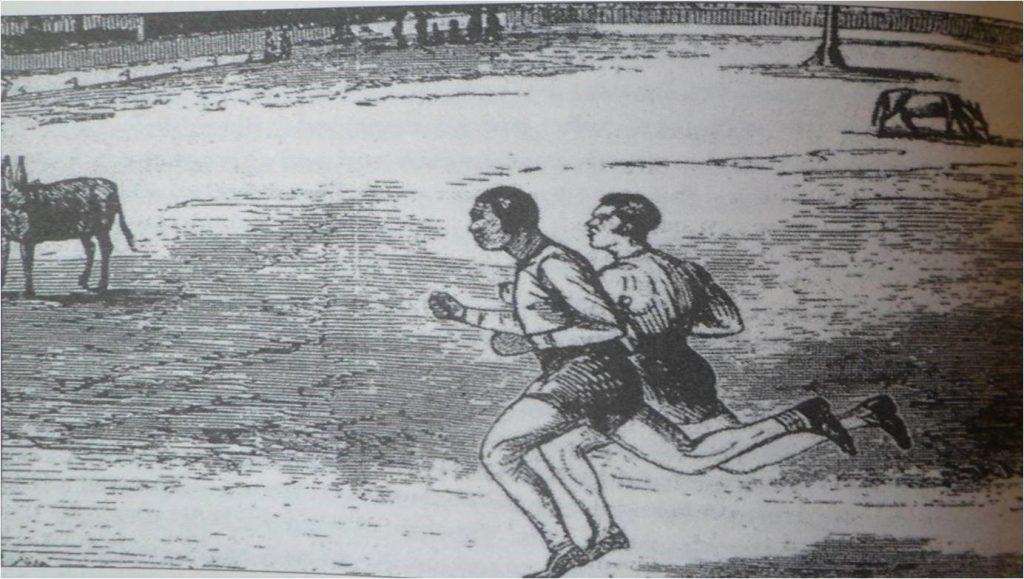

Over 3,000 people came to see him in a race of six miles on the cricket ground, by the Warren House Inn, for a prize of £50. Prices varied between a shilling and six pence to watch the race which was supposed to begin at five pm, but due to late arrivals and crowd crushing did not start until 40 minutes later.

Today, the building that was Warren House Inn still remains, but the running track at the junction of Lindley Moor Road and Weatherhill Road is gone – now a modern housing estate stands in its place.

Deerfoot’s competitors were his great rival John Brighton, the Norfolk milkboy and the veteran William the American Deer Jackson.

Jackson who behind early on and was quickly out of contention. Now the people of Huddersfield could see Deerfoot close up. He had a loping gate, side swinging shoulders and his head moved from side to side.

It was clear to all that Brighton was a much more balanced runner with his cat-like step. Spectators could not help but notice how much smaller the 5ft 2in Brighton was than Deerfoot.

Soon Deerfoot and Brighton were battling it out over 26 laps before Deerfoot put on a late sprint from lap 24, which was his usual style, to win in just over 32 minutes.

As was the custom of this showman, Deerfoot let out blood curdling war whoops as he crossed the finishing line.

Brighton claimed a dog was on the track made him trip over and cost him the race. It proved to be a good contest in the pouring rain.

Commentators noted how well behave the Huddersfield crowd was – this was possibly due to the local influence of Methodists and Baptists.

Despite the initial success of his tour things began to take a downturn by the autumn of 1862. Newspapers reported brawls involving Deerfoot in public houses, though more often than not his fights were either to defend his manager or to protect himself when set upon.

In truth Deerfoot was a quiet thoughtful man who hardly spoke English and who was often found at prayer on a Sunday. He was a practising Christian but this rarely made the press.

Things came to a head when George Martin was taken to court in August 1862 by William Jackson, one of his runners, for not being paid. It was widely reported from the court case that many of Deerfoot’s races, while on tour, were fixed.

The damage was done and touring ended in September 1862. Even though Deerfoot continued to race for another six months his aura with the public was gone.

By this time he had been raced too much by his manager, his form had dipped and his air of invincibility was no more.

Deerfoot had had enough and became tired of the racist cat calling he increasingly had to endure. Most of all, he missed his wife and children in New York State.

However, by the time of his departure Deerfoot’s opponents and the press had come round to publicly appreciating his great talents. Ever eager to play the showman, the great runner raced the crew of The Great Eastern on its deck as it sped back to New York.

In May of 1863 Deerfoot returned to New York with the tidy sum of over £1,000 – more than £550,000 in today’s money. He never trusted banks and had sewn sovereigns into his buffalo coats and skins.

He returned a hero to his Indian reservation in Buffalo and was able to buy land and a farm house. Deerfoot was the wealthiest man on his Seneca Reservation.

Deerfoot never heard from his promoter and good friend George Martin again. In 1865 Martin had a wife, six children and heavy debts, despite all his promotional work. He died, aged 39, in an asylum with symptoms of derangement – all alone and largely forgotten.

As for Deerfoot, he continued to race even into his early 40s. In 1870 records show him racing horses and winning – remarkably he was as fit as he was in his 20s.

Later, as a respected member of his tribe he represented his people at the World Fair in Chicago in 1893, before he died of pneumonia in 1896, aged 66.

By this time the athletic triumphs of his youth, in Huddersfield and throughout England had faded into history.

But those who saw him run, with his bounding gate, never forgot the flamboyant Native Indian runner, who broke records and the will of those who raced against him.

To hear more about Deerfoot, Mount Community Group is holding a talk. Everyone is welcome.

Talk: Deerfoot, the famous champion Native American runner, comes to Huddersfield in 1862

Date and time: Wednesday June 7 at 7.30pm

Venue: Mount Methodist Church, Moorlands Road, HD3 3QU

Entry: £2