By Local Historian Vincent Dorrington

When John Wesley first encountered Huddersfield’s people in 1757 he famously commented: “A wilder people I never saw.”

It was into this world that his great friend the Reverend Henry Venn entered. Venn’s approach was to take God to the people if they did not come to him.

The results were astonishing. Many came to believe that he had saved the soul of Huddersfield.

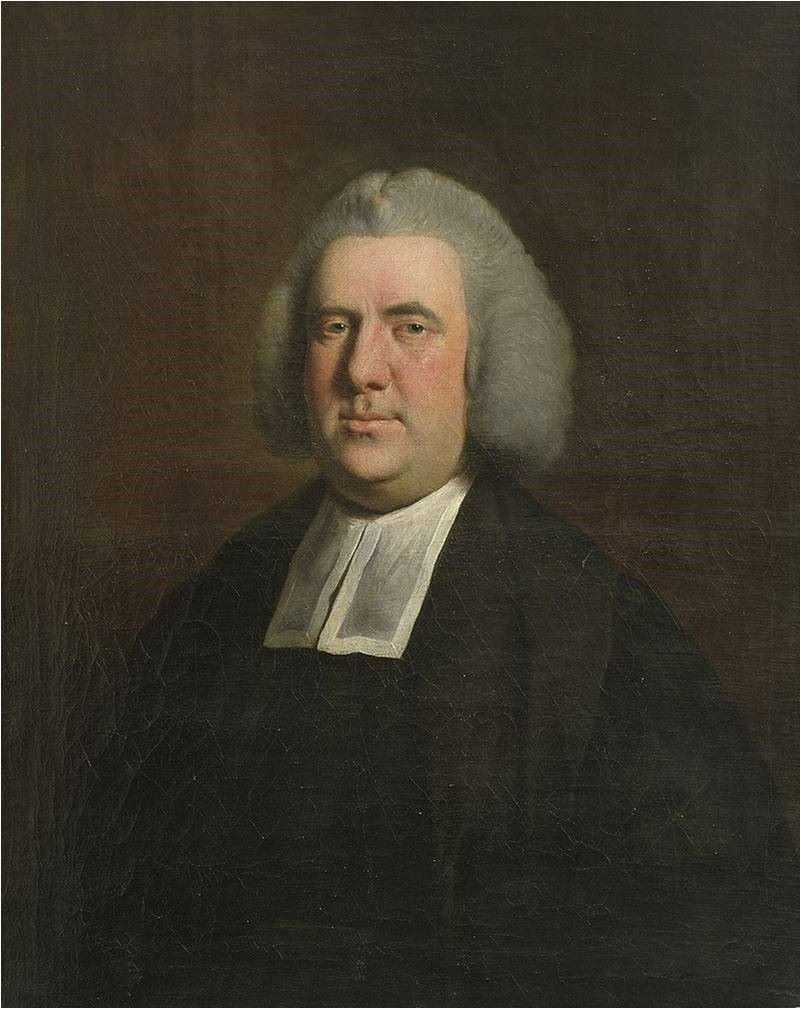

Henry Venn was born in London in 1725, the third son of the Rev Richard Venn. The Venns were a distinguished religious family. A line of Venn ministers could be traced back to the Reformation, with some holding high offices within the Anglican church.

The Rev Richard Venn was vicar of St Antholin’s in London. Like many vicars Venn’s father was serious and stern. He was conventional but he was also loving and principled. Henry was all of these things and more.

At the age of 17, Henry went to Cambridge after winning a scholarship in 1742. He was popular and bright and was known for his cricketing skills. In 1749 he played for an All-England team against Surrey.

However, there was another side to Henry – friends would notice that he went for long walks and seemed troubled.

There was something about the Christian life and its calling that seemed to be troubling him. He spent many hours in prayer and resorted to fasting but his disquiet remained.

Still for the time being Henry’s life took on a set pattern. At the age of 22 he was ordained as a minister in 1747 and two years later he worked as a curate in Cambridge.

A new force seemed to be working in the Church at this time, an evangelical calling to take the teachings of Jesus out from the text of the Holy Bible and into the lives of people.

Henry Venn was in sympathy with this spirit. He accepted the message of John Tillotson (Archbishop of Canterbury 1791 to 1794) that God accepted you when you did your best.

Then there was the influence of the notorious preacher John Whitfield. In the 1740s Whitfield took London by storm with his preaching. Often between ten and twenty thousand people came to hear him preach at Clapham Common as he spoke about God’s mercy and love – Venn listened attentively.

Henry Venn like the other members of the Clapham Sect became transformed by this understanding. Their insight led them to believe that humans were not saved by good works but that good works were a sign that they were saved.

In the 1700s Huddersfield was a small market town surrounded by a cluster of townships and hamlets. Its people were mainly employed as textile workers, mainly working from their cottages.

They were known for their rough manners and independent spirit. Not only did John Wesley call them a wild people, he also said that they served the Devil and would not tolerate the Gospel of Christ.

Other commentators noted that Huddersfield villagers were “given to pugilistic contests, bull-baiting, intemperance and dissipation.”

This may have applied to an element of Huddersfield society but it is also clear from Venn’s conversion rate, that there was spiritual yearning in the hearts of others.

Venn was on mission – he felt the challenge of meeting God’s call by coming to Huddersfield. It should be remembered that Henry Venn came to Huddersfield only two years after John Wesley’s pronouncements.

He himself said that at first things were difficult – that it was like preaching to dry bones, but wonderful things would come of this Egyptian darkness.

Eiling Bishop married Henry in 1757. She too had strong evangelical feelings, and from the start felt that divine providence was guiding her husband. However, moving from fashionable Clapham must have been a shock for her.

Eiling was red haired, fiery and a dominant figure who Henry adored and doted upon. Venn admitted that she was his right arm and that he would not have succeeded without her.

The home of Eiling – the Vicarage – was not to her liking. It was described as being “…a very old building in the worst part of the town with a garden attached in which nothing green would grow … all was hemmed in by tall chimneys and wretched buildings.”

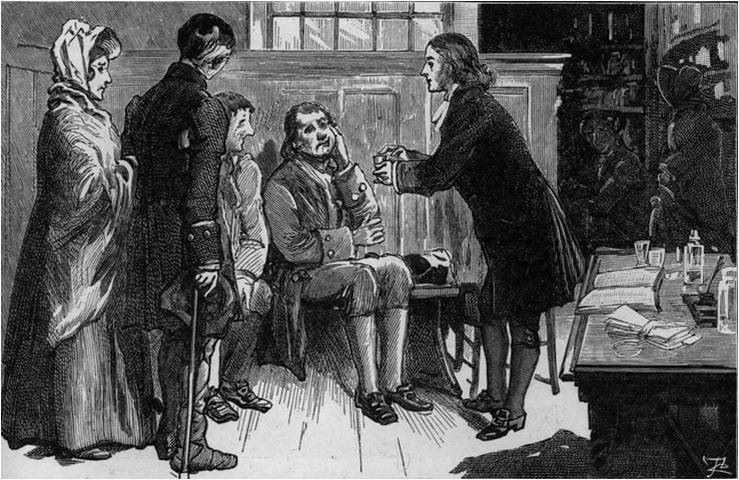

Still the work of God’s minister flourished there. Many parishioners visited Venn in the Vicarage to seek counselling. His maid saw many leave his study with tears running down their faces.

Venn’s generosity was widely appreciated and he often gave money to the needy from his own pocket.

“I care no more for money than dirt,” he was heard to say – often to the frustration of his wife. Venn’s care for the urban and rural poor was obvious.

The people of Huddersfield soon found the Reverend Venn to be a remarkable man. He had emotional intelligence, was able to read people and befriend them quickly.

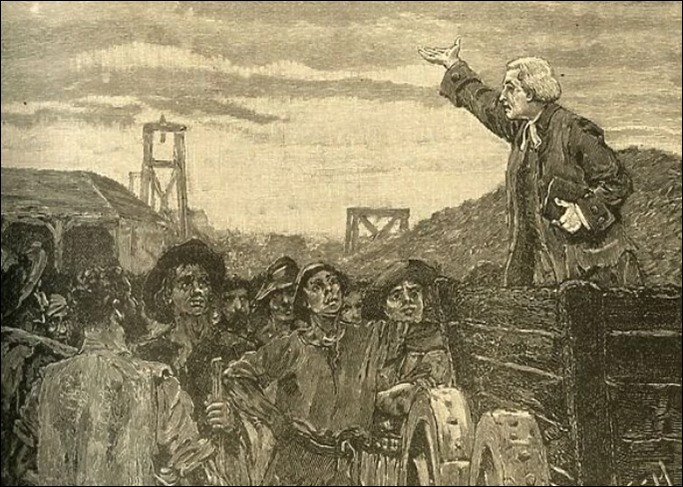

Parishioners observed that he looked as if he would jump out of pulpit when preaching. Once he had found his inner confidence his preaching style took on a theatrical format.

At first he was stern and trembling as he berated his listeners by telling them they were all sinners and breakers of God’s law. Then he would tell them that they should live in fear of God’s righteous wrath.

A transition would take place as Venn’s sermons progressed. His face would change into a benevolent smile and tears would run down his cheeks.

Congregations would be taught of God’s loving mercy in sending Jesus. Salvation was open to all people of faith. Most importantly was the message that it was God who saved mankind.

At first, some 300 parishioners turned up to hear their vicar when he preached – mainly out of curiosity. Numbers doubled to 600 the next week and this number remained the norm for whenever Henry Venn preached.

His services were full of human warmth with an emphasis being put on his love of church liturgy and good singing. Huddersfield had never known anything like the Reverend Venn. People came as far as Brighouse, Halifax, Leeds, Haworth and Penistone to hear his message.

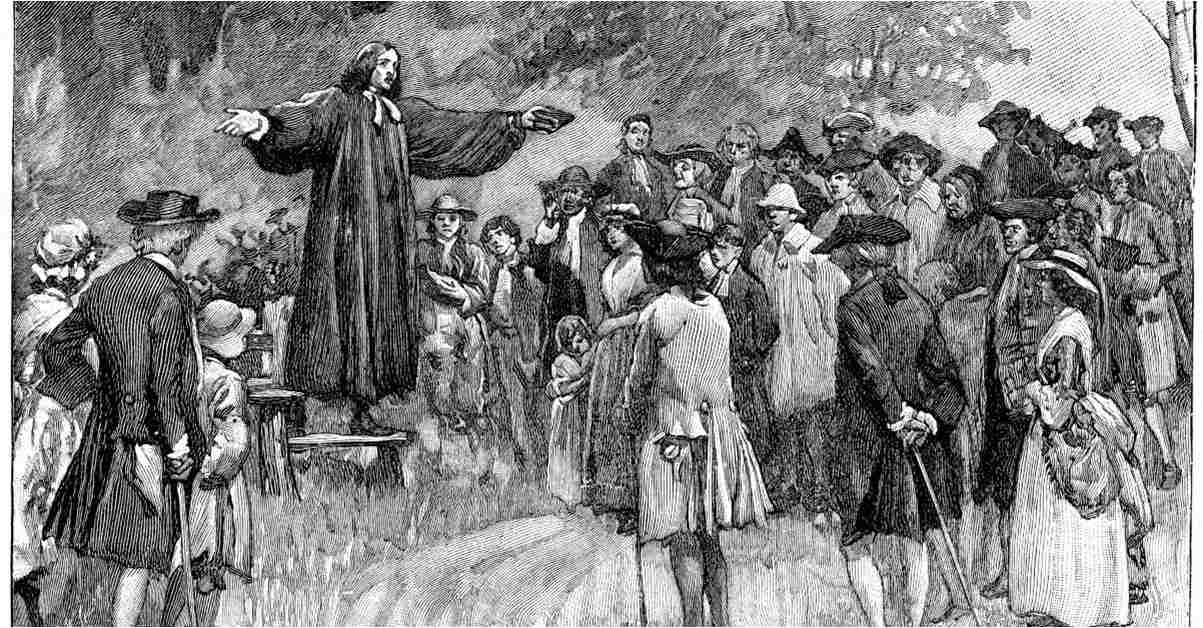

The great evangelist also took his message outside the parish church to the townships and hamlets of Huddersfield.

Many a time he would ride to an isolated barn or farmhouse in lonely hamlets, to hold Bible reading groups or to provide pastoral care to his flock.

Even the number of church attendees from the established Baptists at Salendine Nook declined as some of its congregation came to listen to Venn’s teaching.

Sometimes he taught outside the parish boundaries of Huddersfield which irked local clergy but he was prepared to travel wherever he felt he was needed.

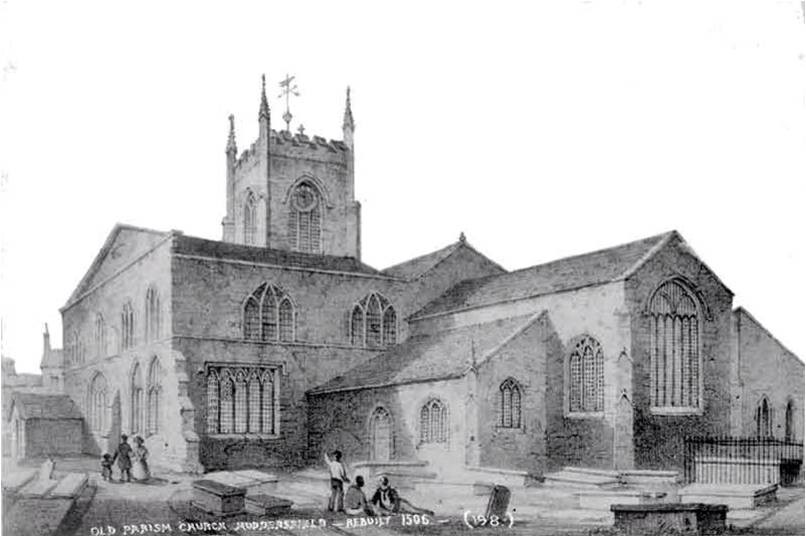

Venn brought the evangelical spirit of the Clapham Sect to Huddersfield. At first, he allowed Methodists to preach in his parish at least once a month and in 1765 even allowed John Wesley to preach in St Peter’s.

Other famous Methodists like theologian John William Fletcher of Madeley, was renowned in Britain for his piety and generosity. When asked if he had any needs, he responded: “…I want nothing but more grace.”

Perhaps the most famous preacher to visit St Peter’s was George Whitfield, who Henry Venn seemed to admire him most all.

Whitfield crossed the Atlantic many times to spread Methodism in the United States, especially to native Americans in Georgia. Some hundreds of people were said to have filled St Peter’s to hear him preach and to view his lazy eye for themselves.

Those who encountered Whitfield commented that this was the eye of God. It gave the impression of always being fixed on those who came to his sermons, no matter where they sat were church.

When Whitfield died in 1770 Venn gave the sermon at his funeral. Their eyes may have been different but they shared the same religious vision.

By the late 1760s Henry Venn’s life took a downturn. His wife died of cancer in 1767 which devastated him.

Increasingly the grieving Venn felt isolated and depressed. His own health began to fail as he suffered from chest pains and lung problems which he felt was brought on by overwork.

The weakened preacher could only preach every fortnight and even then it took him two or three days to recover from his exertions. His strong voice had become ruined due to extensive preaching.

For several months Venn took himself off to Clapham to recuperate. However, Venn felt certain that he did not have long to live. To save his health, he sought a quieter and less stressful appointment in the countryside.

The people of Huddersfield were greatly saddened but also confused and shocked. Still they flocked to St Peter’s in the final few weeks before his departure.

Venn had made many friends among the district curates and populace, but all attempts to persuade him to stay on failed. In 1771, Venn was forced to retire from his parish at the age of 46.

To his great surprise Venn lived another 25 years and he remained a man of importance in the Church of England.

He was made a Fellow of Kings College, Cambridge and his fame was such that future ministers constantly sought out his guidance and instruction.

Venn never forgot Huddersfield and with his son, John, returned to his old parish in 1780. He was warmly greeted by his old congregation but things had changed.

His successor was not inclined to the evangelical path to Protestantism and adopted a more orthodox Anglican approach.

Debate still continues among academics as to whether Venn was a Methodist or not. He certainly wanted Anglicans and Methodists to work together and he supported Methodist ministers.

Venn remained an Anglican but he did prove to be a major figure in the founding of the Methodist Church.

Venn did not want a new denomination like Methodism or Independents challenging the Church of England. He did regret his lack of statesmanship in this matter.

In time he came to question his contribution in supporting his followers who set up the Nonconformist Independent Church in Highfield, only a year or so after he departed Huddersfield.

This was clearly a reaction by some of Venn’s supporters to the new minister at St Peter’s. It was the first Dissenters’ church to be built in Huddersfield.

The Venn genes were also remarkable and continued to make their mark in society after his passing. His great grandson was the famous mathematician John Venn, who developed the Venn diagram and the famed writer Virginia Woolf, was also a descendent of his family line.

Venn Street, the location of the old Vicarage from where Henry Venn laboured so hard, only just survives at one end of the entrance to the Kingsgate shopping centre car park.

The St Peter’s of Venn’s day was demolished in 1836 to be replaced by the current parish church. Inside, on its northern wall, can be found a memorial to the Parish Church of St Peter’s most renowned minister – Henry Venn.

Vincent Dorrington will give a talk ‘The Life and Times of the Rev Henry Venn’ on Wednesday March 6 2024 (7.30pm) at Mount Methodist Church, Moorlands Road, Mount, HD3 3QU. Entry is £2.