By Local Historian Vincent Dorrington

In 1920 Victor Grayson, the ex-Colne Valley MP and political firebrand went missing, never to be seen again.

With this startling news a political mystery was born that to this day remains unsolved. The life and times of Victor Grayson warrants recalling – not only for his disappearance, but also as a tribute to a political maverick and unique individual.

Albert Victor Grayson was born in the slums of Liverpool in 1881. His parents were William Grayson, a carpenter and Elizabeth (Lizzie) Grayson.

They had 10 children in all – Victor was supposedly the seventh boy to be born. Victor appears to have been an intelligent but nervy child with a stammer.

His classmates poked fun at him, but Victor’s time was taken up with reading Westerns and attending church – he was resilient and nobody’s victim.

Siblings often saw the young Victor standing on a stool speaking to a street audience – clearly watching religious and political orators on street corners and at the docks had an impact on the growing Victor.

His mother Elizabeth was a deeply devout religious woman and had high hopes that Victor would use his speaking skills to become a Unitarian minister and missionary.

Whatever the case Victor was a restless youth who felt there was more to the world than Liverpool. At the age of 14 he stowed away, with a friend, on a ship headed for South America.

After three days they were discovered and the ship returned them to dry land at Tenby in Wales. He then proceeded to walk 165 miles back to his home town, often sleeping in barns and on hayricks. He even slept in a workhouse, where the authorities took pity on the stray.

Victor then left school at 14 and at first worked as an apprentice engineer for an established company at Liverpool docks – he served three of his seven-year apprenticeship there but the prospect of working in a factory for the rest of his life horrified him. Victor wanted to be a preacher to save his class from the social evils in which they found themselves.

At the turn of the century Victor seemed to be following his mother’s wishes. He gained experience of speaking and even preaching at Missionary meetings. Gradually he lost his Liverpool accent.

In 1904 he started at Owen’s College at Manchester University – to train as a minister. And yet things were not set in stone.

Before going to college Victor had trained as an engineer. He quickly involved himself in union concerns and this led to his political awakening.

The poverty and hardship of life on the streets and in the slums of Liverpool haunted Victor – he was outraged by the social injustice and felt that immediate change was necessary.

Inevitably the rise of socialism and the Labour Party in the early 1900s inspired Victor. He joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and quickly gained the reputation of being an inspiring orator.

1907 proved to be a formative year in the life of 25-year-old Victor Grayson. Against all the odds he decided to stand in the Colne Valley by-election against Liberal and Conservative rivals.

This greatly angered Keir Hardy, the leader of the Labour Party. There seems to have been an unofficial understanding between the Labour and Liberal parties – they would not stand against each other where one party was clearly stronger than the other. This would give them a better chance of defeating Conservative candidates.

Victor Grayson had no time for this political truce, so he decided to stand in the Colne Valley by-election as an Independent Labour candidate.

He chose wisely because the Colne Valley was more than receptive to give him a good hearing. The area was strongly non-conformist and its ministers felt that Grayson’s ideas for social justice were well in tune with the teachings of the Bible.

Emily Pankhurst and the Suffragettes also threw in their support for Victor as he spoke out against the political and social injustice women had to face.

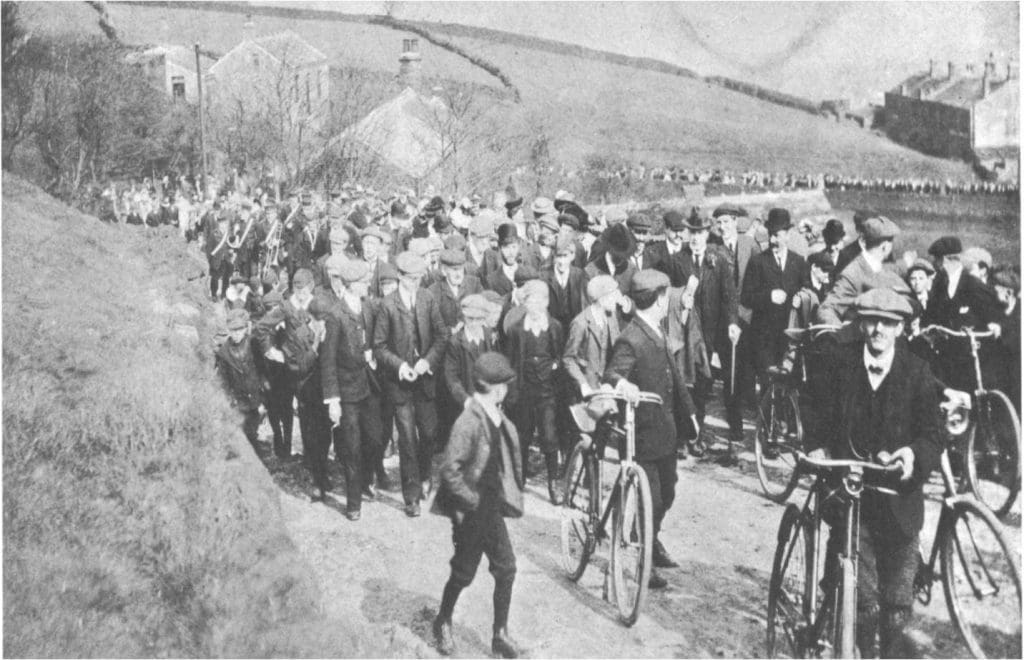

Despite the lack of backing from the Labour Party, Grayson was able to gather funds to fight a dynamic election campaign in 1907.

Supporters gave money and sold their watches and precious possessions. Women working in the mills donated their pennies.

However, it was Grayson’s amazing powers of oratory that helped him win this election. He spoke of a socialism that would bring benefits to the people. They would have decent wages, the unemployed would be financially supported.

A national insurance scheme to look after the health of the nation would be provided and women would be allowed to vote.

Grayson would travel throughout the constituency with a horse and cart. The cart acted as his platform as he criticised his opponents and spoke about the brave new world he would help bring about.

Literally thousands came to hear Victor Grayson speak. The stammer was gone to replaced by a flowing and passionate eloquence.

Those who heard him speak were often transfixed by his almost missionary zeal. Others remembered his shock of golden hair, pumping fists and sartorial elegance.

A strange socialist said his opponents with his attire of a ‘toff’ – top hat, overcoat, cane and monocle. Victor Grayson seemed to come out of nowhere with his meteoric rise and looked nothing like a working class politician.

The Press, especially in London, were startled and alarmed by Grayson’s socialist victory – what would it lead to – a red revolution? Their concerns were unfounded.

Grayson was at odds with Keir Hardie and the Labour Party at Westminster over their lack of radicalism. Even more so was Grayson’s outright hostility against the Conservative establishment.

In 1908 he was escorted from the Chamber due to his outspoken opposition to state money grants being given to diplomats of the Empire.

Twenty times the Speaker of the House asked Grayson to stop interrupting procedure before he had him removed from the House.

As this happened Grayson turned on Labour MPs and called them traitors for not defending the plight of the starving poor.

Victor Grayson spent little time in Parliament for the next two years to the dismay of his Colne Valley constituents.

Most of his time was spent attending rallies in support of workers and strikers. It came as no surprise when he lost his seat in 1910, being beaten into third place by the Liberal and Conservative candidates.

The next few years proved to be difficult for Victor. He had money problems and close friends noticed how his love of whiskey affected his judgement.

Reports of his failure to turn up at meetings or of his being dragged off platforms because of his drunken state caused alarm. The great defender of the people’s rights and enemy of capitalism and the Empire was on the decline.

Things seemed to improve for Victor when he married beautiful actress Ruth Nightingale in 1912. By 1914 they had a daughter, Elaine, but Victor’s health gave way due to economic stress.

It was only with the help of Ruth’s father (a Bolton banker) that the young family could keep their heads above water.

The outbreak of WW1 seemed to put a strain on Victor’s standing among socialists as he supported the war.

With government backing he went on a lecturing tour (taking his wife and baby) to the USA in 1914 and then to Australia and New Zealand in 1916.

It appears that the British government used him as a drum master for recruiting Commonwealth soldiers.

In 1916 he joined the New Zealand Army after being challenged to do so while speaking during a rally. Victor suffered from shell shock and also shrapnel wounds at the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917.

By 1918 Victor was back in England where bad fortune continued to dog him when his wife and daughter died during childbirth. This was a terrible blow so Victor withdrew from public life.

Money problems continued to beset him – Victor’s only means of income came from his writing of infrequent journalistic articles.

By 1920 Grayson seems to have had an uplift in his economic fortunes – he was living in an expensive apartment in Piccadilly and living the good life – a shortage of money no longer seemed to be an issue.

It was clear that a lucrative and regular source of income was making its way to him. This has been a source of endless interest and speculation among political writers.

One theory is that Grayson had involved himself in blackmail to support his lavish lifestyle. The chief candidate is believed to be Arthur Maundy Gregory.

This colourful character was a theatrical impresario and had important contacts with government and royal officials.

He claimed to be a member of MI5 and to have secret knowledge of the private lives of key figures. Though a one time friend with Victor, they had fallen out badly by 1920, probably because Victor found out Maundy Gregory was spying on him.

In a Liverpool speech Grayson announced that he would be revealing the identity of a monocled dandy in Whitehall who was making a fortune out of the sale of peerages and knighthoods.

This was Gregory who was acting as middle-man in raising funds for Lloyd George and the Liberal Party.

Clearly Gregory had to shut up Victor before news of this scandal got out. Just a few weeks before his disappearance Grayson had been beaten up in London as a warning to keep his silence.

Researchers have pointed out that Maundy Gregory may have had other motives in getting rid of Victor Grayson.

It is claimed that Grayson knew about influential members of the establishment who were homosexual and that he was blackmailing them.

Maundy certainly had his contacts and claimed to be a member of MI5. Writers have suggested he was ordered to spy on Grayson because he was a danger to national security.

Grayson was said to have contact with Irish nationalists. An even greater perceived danger was that Grayson was a communist in contact with radicals who were prepared to spread revolution in Britain. He had to be got rid of and Maundy Gregory was the man for the job.

Whatever the potential reasons for making Victor Grayson disappear, there is no doubt he did disappear in September 1920.

Over the years there have been accounts of Victor’s last day. One is that he was having drinks with friends in a London hotel – The Strand – when he was called to a phone to meet someone in a hotel in Leicester Square.

On leaving he told his friends he would be back in a short while. In his book ‘Murder by Perfection’ (1970) journalist Donald McCormick states he has evidence for this and much more.

He claims that the person Victor met was Maundy Gregory and that he was seen leaving the Leicester Square hotel with two men carrying two suitcases.

McCormick then claims that Victor was seen again on the very night he went missing, 28th September 1920.

The witness was the artist Arthur Flemwell, who was painting the River Thames, when he saw Grayson and Maundy Gregory enter a bungalow, No 6, The Island, Thames Ditton – near Hampton Court.

McCormick said Flemwell was certain it was Maundy Gregory with Victor because Gregory had sat with him for a portrait earlier.

Flemwell then told McCormick that the following day he knocked on the door of the bungalow. A woman then told him most vehemently that Victor Grayson had not been a visitor the previous night.

Andrew Cook in his book ‘Cash for Hours’ (2013) casts doubt on this account and calls into question McCormick’s reliability.

Another and more reliable account of Grayson’s disappearance comes from Hilda Porter. She was the manageress of Grayson’s apartment in Vernon Court in London.

She claimed that every two weeks a package for Grayson was delivered by two men in uniform. Grayson told Porter the package contained money.

One morning in late September 1920 – she did not remember the precise date – two strangers came and asked for Grayson.

After spending most of the day with Grayson, they left together carrying two large suitcases. Grayson told her: “I am having to go away for a little while. I’ll be in touch shortly.” That was the last she saw of Victor Grayson.

It is unclear how these two accounts that share some similarities relate to each other. Did Grayson’s meeting with his friends at a Strand hotel come before or after Hilda Porter’s encounter? There is no way of knowing.

There was some indication in 1921 that all was not well. His Unitarian College in Manchester declared that Victor Grayson was deceased, but no evidence in college archives suggests why this was so or who had notified the college that Victor was dead.

Just as there have been many sightings of Lord Lucan after his disappearance the same is true of Victor Grayson.

However, Grayson’s supposed sightings have a greater sense of authenticity. None more so than a strange sighting at Maidstone in 1924.

A young radical orator named John Becket was approached after speaking to a crowd close to Maidstone prison.

The man was tall, thin and well dressed. Becket remembers the stranger saying: “That was some speech, sonny. I used to just give them the same stuff.”

He then took Becket and his fellow speaker, Seymour Cocks, to a hostelry. Here he spoke about Ireland and then of war.

He spoke of his time in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Cocks noticed that the man was shaking while talking and most probably had been suffering from shell shock.

Philip Snowden, the MP for Colne Valley in 1922, was approached by the Maidstone witnesses. He knew Grayson and was of the opinion that young Becket and Cocks had indeed met Victor Grayson.

Later Becket was shown photographs of Victor Grayson and confirmed that the man that he met in Maidstone was indeed Victor Grayson.

Another strong sighting merits a closer examination. Lord David Clark in his recent book gives some weight to Victor Grayson being alive after 1920 and even living a double life until the 1950s.

He claims that Ernest Marklew, MP for the Colne Valley in the 1930s, tracked down Victor Grayson to a furniture shop in Kent that he owned.

Upon being discovered Grayson begged Marklew not to reveal his new identity or whereabouts. Just before his death Marklew is supposed to have passed on this information to a Labour MP.

The furniture shop link is further supported by a letter sent to the Mayor of London in 1933. A man who knew Victor Grayson saw him on the London Underground and followed him to a furniture shop on Oxford Street.

Adding to the intrigue is an old open envelope from the early 1930s that came into the possession of Derek Forwood who was investigating Victor Grayson in the 1960s.

It belonged to the Dale Manufacturing Company who were furniture dealers at 473 Oxford Street, London. Along the company address were the words ‘Personal, Victor Grayson.’

A socialist activist had written to this Victor Grayson in the 1930s. The letter of reply denied being the politician Victor Grayson, but the handwriting had many similarities to that of Victor Grayson. It is highly probable that Ernest Marklew attended this address in his search for Grayson.

Over the years other credible witnesses have claimed to have knowledge of Grayson. These ranged from his Colne Valley agent who claimed to have Victor’s address in London and that he was in contact with him. Even a CID detective in 1948 claimed to be in contact with Grayson.

Grayson’s war medals while in the service of New Zealand are seen as an indicator by Lord Clark as, a smoking gun, a sign that Victor was alive in 1939.

They were collected from the Ministry of Defence in 1939 and signed for by a Victor Grayson. Victor’s family had no knowledge or connection with this incident.

In order to collect these medals clear and significant paper work and identification from Victor Grayson would have had to be provided. The implication is that it was Victor himself or someone with his private documentation.

Also in 1939 Sidney Campion (as youth work for ILP but now work in Parliament) claimed to have seen Grayson on the District Line of London Underground with young glamorous woman as they boarded the train at Sloan Square.

Campion said the woman referred to the man she was with as ‘Vic’. Campion told of his encounter to the press corps at Parliament, who then spread this story.

Clearly those in authority were showing a growing interest in Victor Grayson by WW2, probably spurred on by Campion’s wide press coverage.

Reg Groves (Labour journalist) in 1942 was called into Scotland Yard for questioning on the orders of the Cabinet.

Papers belonging to Groves were never returned to him. In the 1930s Groves had been trying to trace Victor Grayson after hearing from Labour comrades that he was living and working in London.

Groves claimed that the police told him that Grayson had given up socialism and booze, had married a wealthy younger woman and was working in business/banking in Chelsea area.

The Met denied at first denied carrying out an investigation into Grayson. They later changed their story saying that if they had had any papers they would have sent their findings to National Archives – they denied having received any such papers.

The Met then said records had been destroyed but on whose orders they could not say!

In 1946 Reg Groves wrote ‘The Mystery of Victor Grayson’ which sold 10,000 copies in 12 weeks. In it he speculated Grayson could still be alive. Groves admitted to being frustrated by Grayson’s family destroying most of his private papers.

Reg Groves later revealed that in 1942 another figure showed an interest in Victor Grayson – Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

He asked to see the files on Grayson from the Metropolitan Police. These records were never returned and presumably lost. An obvious question was why a busy man like Churchill was expressing an interest in Grayson.

Some researchers believe that Churchill had discovered that Grayson was a secret service agent working for MI5 or MI6 and that he wanted to find out more information about him.

Another line of inquiry implies that Churchill had come to know the rumour that Victor Grayson was related to Winston Churchill.

Newspaper articles from the 1920s relate that Elizabeth Grayson reported that Victor was not her naturally born son.

She said he was indeed the illegitimate son of John Spencer Churchill, the 8th Duke of Marlborough and uncle of Winston Churchill.

It is clear that controversy surrounded Victor Grayson in life and death. It is possible that the truth of Victor’s disappearance still lies in the files of Scotland Yard or the Home Office.

His life story is surrounded by ifs, buts, rumours and speculation. Mystery will always surround him, but what cannot be doubted is that he was a unique character who has left his mark on Britain’s political life.