By Vincent Dorrington

Ainley Top, these days, is probably only heard about when there are traffic problems on the M62 as the village meets the motorway at Junction 24.

While it is true that road systems, stemming back to Roman times, have characterised this hamlet, there is much more to the village of Ainley Top than meets the eye.

At its high point standing 800ft above sea level, with commanding views over Elland and the Grimescar Valley, the location of Ainley Top has long played a significant part in local history.

Roman legions, based at Outlane, marched on its lower road, as they tramped between Chester and York. Before the Saxon defeat at Hastings, Norsemen came to the area in the 900s.

Ainley is partly a Norse name meaning ‘Agwind’s clearing’. His lands, which were mainly wooded, ran up from Elland to Ainley Top, Rastrick, Fixby and then Lindley. They became known as part of the Ainleys.

Many travellers, including Cistercian monks, used the local ridge-ways to carry salt from Cheshire. Strong connections can be made with this religious order and their trade routes at nearby Haigh House Hill.

It is not until the 1200s that we find written historical records referring to Ainley Top. A house and small estate, known as Knowles, at the bottom of Ainley Top hill, dominated the area.

Wakefield’s court rolls, from the 1300s and 1400s, tell of a common border between Ainley and the Knowles, and tension between their rival tenants. Maps from the 1770s clearly show Enley (Ainley Top) and the Knowles to be separate estates.

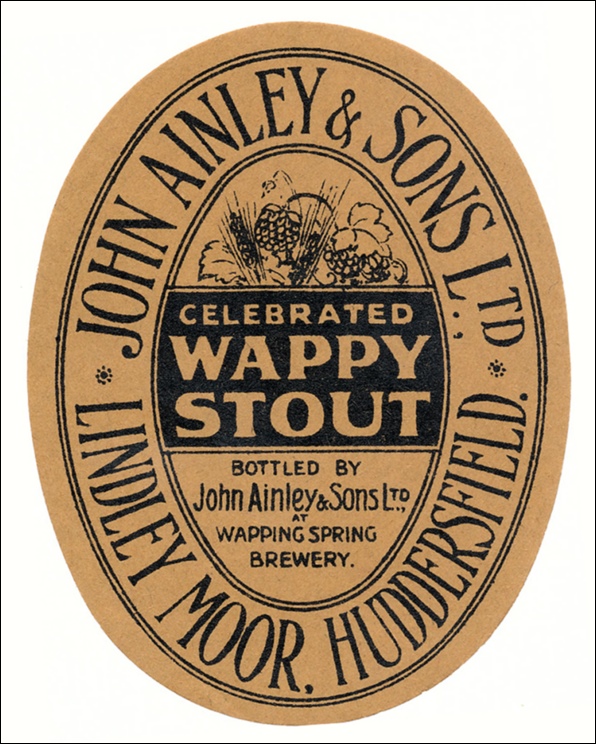

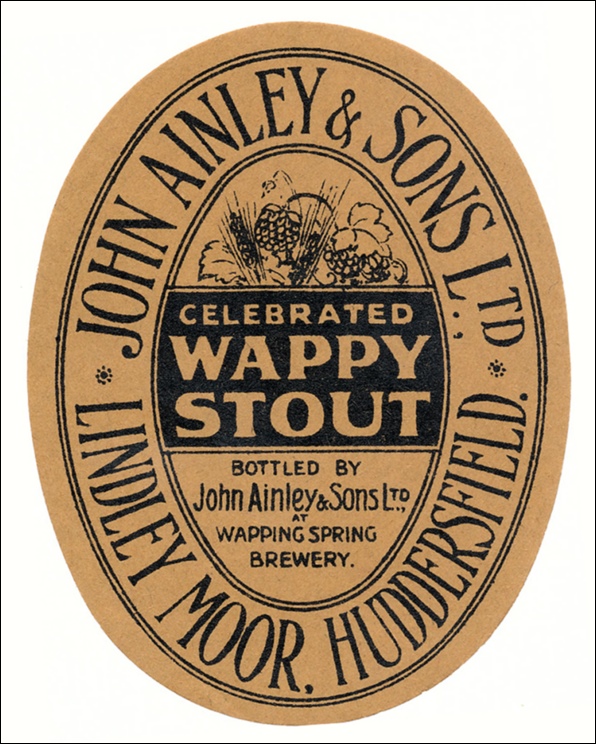

The Ainley surname came to dominate the Ainley area from early medieval times. Today, over 80% of families with the surname ‘Ainley’ are found in England and most of these come from West Yorkshire. John Ainley and Sons, who came to own the Wappy Spring Inn and Brewery on Lindley Moor Road, come most readily to mind.

From the 1700s major roads, especially the turnpikes, came to have an impact on Ainley Top. In 1777, Blind Jack of Knaresborough directed the building of the Huddersfield to Halifax turnpike road.

This was followed by the New Hey to Huddersfield turnpike with its spur running through Ainley Top in 1806. A cast iron mileage stoop can still be found today on this section of road. The final great turnpike to run near Ainley Top was built in 1824 – connecting Huddersfield to Elland.

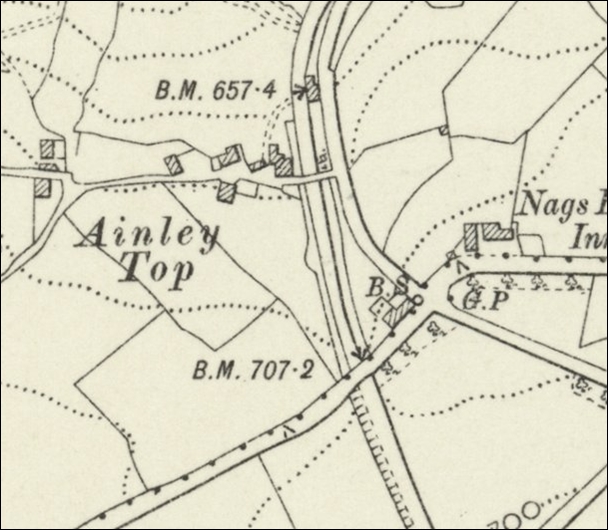

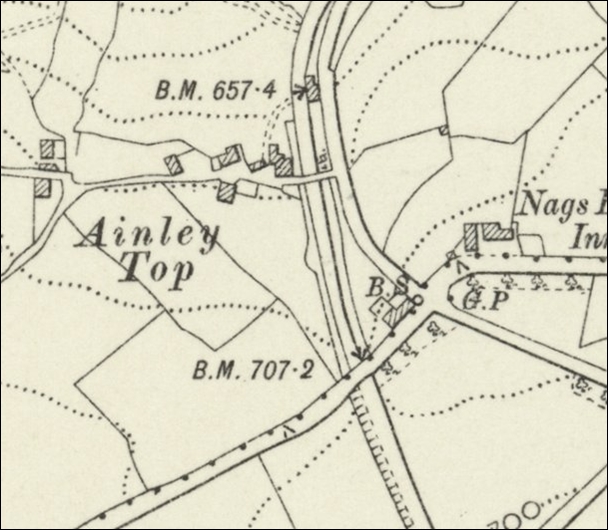

OS maps and aerial photographs show the two great bridges at Ainley Top, built in 1824, to accommodate these changes.

The top bridge, which connected Lindley Moor Road to Ainley Top, was called Ainley Bridge. When the bridge was replaced in 1970 its capstone (dated 1824) was placed in the roadside wall of the Elland Bypass, where it can still be seen today by the bus shelter.

No sign of the lower bridge (Whitehaughs bridge) that served Lower Ainley Top remains today. It was destroyed to make way for the M62 bridge.

Evidence from OS maps of 1900 show how this bridge connected both parts of Ainley Top that was separated by the turnpike road built in 1824.

The 1800s saw the peak of mining in the Ainley Top area with at least seven mines in operation, stretching from Birchencliffe to Blackley and down what is now the Elland Bypass.

Many people living at Ainley Top must have been employed in the mines as well as farming. In 1842, a fire-damp explosion in one of these mines killed one person and injured nine others, one being a 15-year-old boy from Birchencliffe.

Another time when the mines of Ainley made national headlines was when they took part in the National Coal strike of 1912.

Colliery pits still remain and can be a cause of danger. Local headlines from 1958 describe how a collie dog fell down a 40ft pit shaft and had to be rescued by a fireman using ropes.

The political life of Ainley Top has aroused much interest. Residing on the border of Halifax and Huddersfield has meant that some residents vote in Calderdale elections while others vote in Kirklees.

In the early 1800s, the politics of Ainley Top residents was not radical, unlike much of Huddersfield. This was possibly due to the conservative views of local landowners, like the Thornhills of Fixby Hall, who gave employment to many local people.

No nearby mill of consequence gave employment to the people of the hamlet, so there was no call for factory reform or support for the Luddite cause.

It should come as no surprise when the grandson of James Radcliffe bought the Nag’s Head without any local opposition.

Radcliffe’s grandfather was notorious and despised by many Huddersfield people. He had been responsible for the capture and execution of the Luddite radicals, who shot the mill owner William Horsfall, in 1812.

The location of this hillside hamlet played a significant role in the Huddersfield election of 1834. A large army contingent was secretly placed in Elland, in case Huddersfield radicals caused civil unrest.

A beacon was placed at the top of Ainley Top. Should riots break out in Hudderfield, a beacon was to be lit there.

Once spotted at Ainley Top, its beacon was to be lit, where it could be seen at Elland and the army could be called for assistance. As things turned out, the troops were never called upon.

Perhaps the Nag’s Head Inn is the most famous building at Ainley Top. Originally it was two cottages built over 300 years ago. It was converted to meet the growing number of stage coaches travelling through the area. A barn adjacent to the inn today, could well have been used for stabling.

In Victorian times, walkers and day trippers walked up through Ainley Fields, across Whitehaugh bridge and up to the hamlet and then along Lindley Moor Road to the inn on New Hey Road.

Other walkers came from the picturesque Grimescar Valley to have refreshments at the famous Nag’s Head.

There were many visitors to the inn, ranging from cycling and athletic clubs to the Colne Valley Beagles with their horses and hounds.

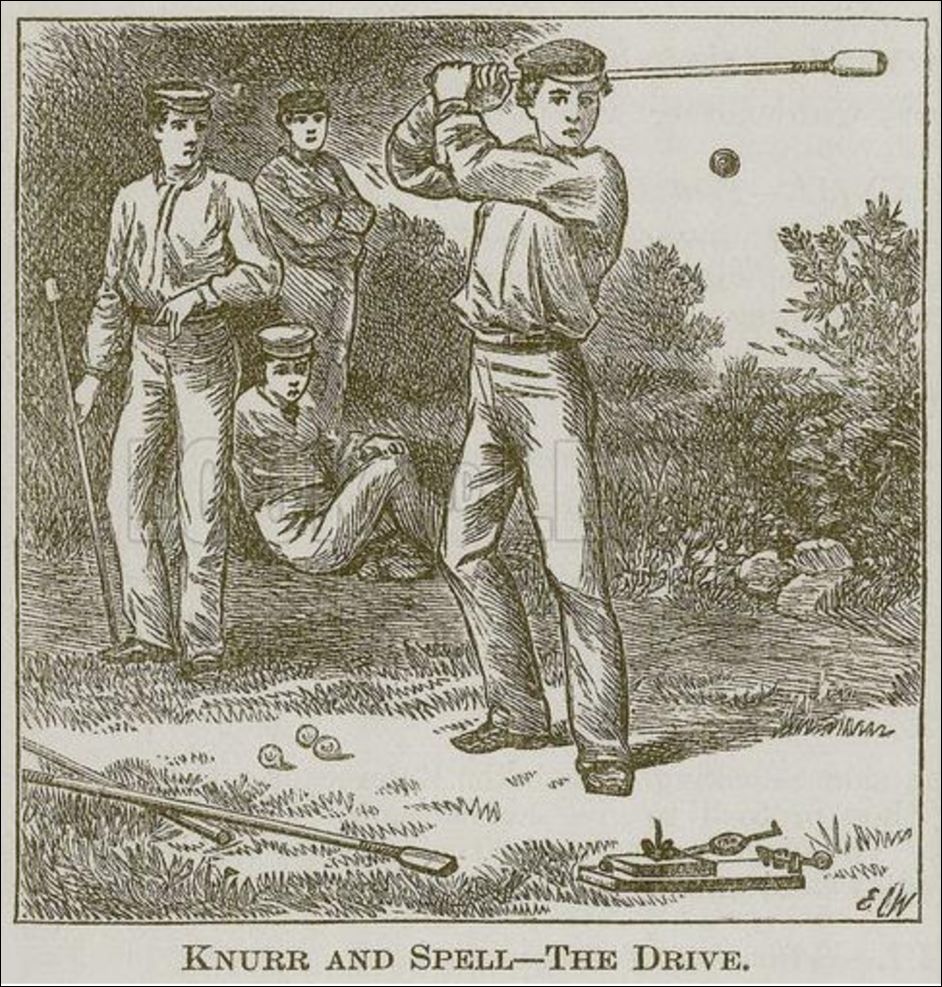

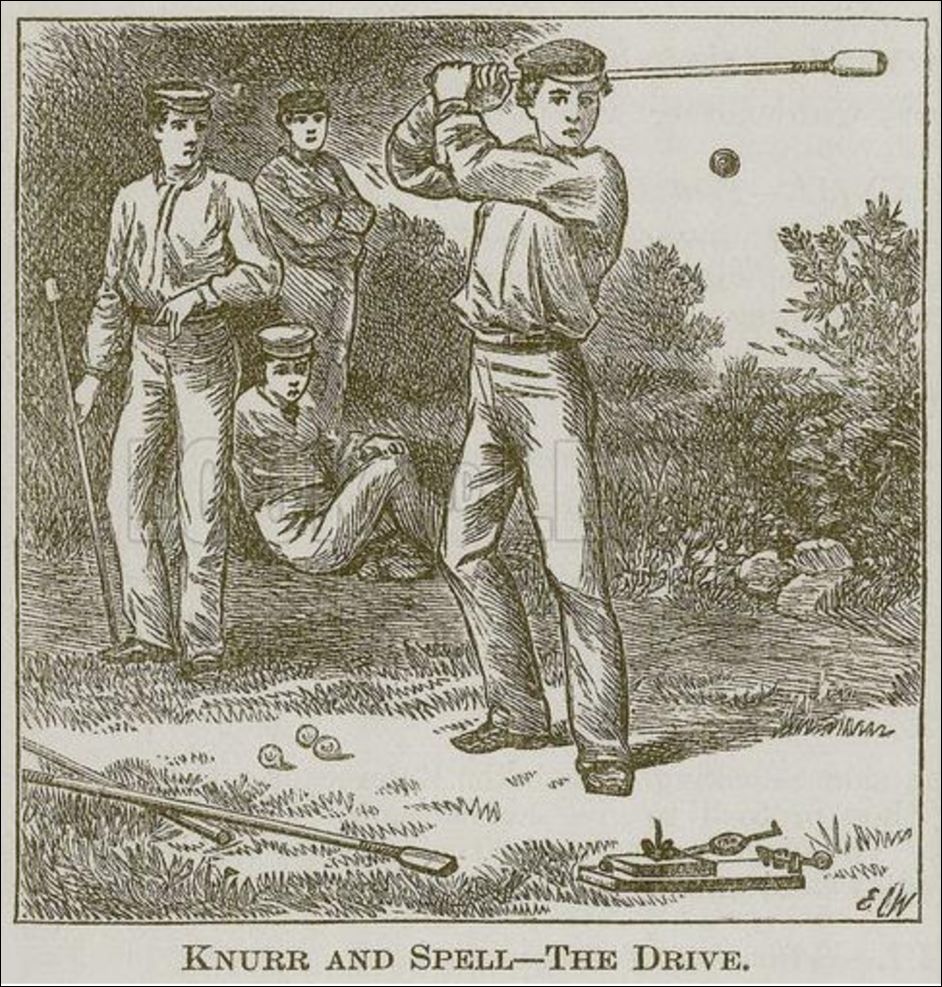

Perhaps most popular of all were the ‘knur and spell’ challenges held on the fields at the back of the inn. Most people came to place their bets on local champions. The rivalry with the Wappy Spring Inn was particularly keen.

Sarah Clough was undoubtedly the longest running publican at the Nag’s Head. She came in 1922 with her husband Sam. He died the following year but left a legacy – the ivy covering of the front walls.

The pub, in 1922, was a free house and came with a barn, orchard and three acres of land on which Sarah kept hens, turkeys and geese – even a pig at one stage.

The main entrance went straight into a small, pleasant bar with the lounge area to the left and the taproom to the right. Sarah Clough, with help from her family, then ran the inn until 1960, when she died aged 87.

From 1970 rapid changes came to Ainley Top, especially with the coming of the M62 and later the Elland Bypass.

The marked increase in traffic provided an opportunity for businesses. By 1972, the Saxon Motor Hotel, with its 120 rooms and costing £500,000 to be built, was opened by Yorkshire and England cricketer Fred Trueman, nicknamed Fiery Fred, remembered as one of the greatest fast bowlers of all time.

Oddly, it paid rates to both Kirklees and Calderdale. The hotel’s restaurant and service block were in Kirklees while main part of the hotel was in Calderdale. Over the years this hotel has changed its name to the Ladbrook Mercury, Hilton Pennine National and, now, the Cedar Court.

However, residents at Ainley Top were more opposed to the building of the Brewers Fayre Pub with its car park for 97 cars.

They made sure the area was landscaped and did not encroach on the historic Knowles area of Ainley Top. Today the Toby Carvery has replaced the first pub/restaurant to be built on the site.

Residents of Ainley Top have fought long and hard for the interests of their community – sometimes they won and sometimes they lost.

In the 1930s proposals were put forward to build a dog race track but locals defeated the move.

Between Crest Road and Stanley Road was a play area used by residents for 40 years. In 1990, the landowner wanted to build on the land.

Despite appeals made to Calderdale Council, the residents lost. However, they were victorious in having the road running through the village narrowed and stopped it being used as a rat run.

In recent times there was controversy over land off the Rastrick and Brighouse Road being sold to developers.

Most drivers, on the M62 or the Elland bypass, travel past Ainley Top, oblivious of its existence. Yet this village enclave has endured, and guarded its long history for centuries.