By Vincent Dorrington

A visit to Buckstones Edge is high on the list for Huddersfield day trippers.

Many travel along the A640, Huddersfield to Oldham Road, to admire the panoramic views over the moorland to Marsden. Others go to watch the hang gliders flying.

Few know of the grim tragedy that took place on these desolate moors in 1903, when a double unsolved murder took place, that shocked the country.

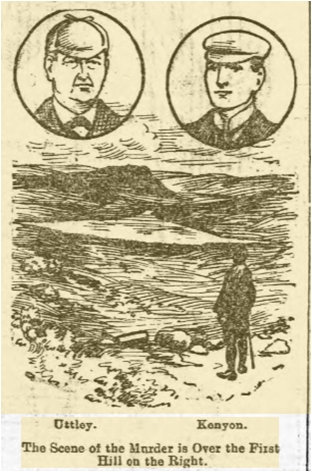

On Thursday September 10 1903, the bodies of two gamekeepers were found. The first victim to be found was William Henry Uttley.

Uttley was aged 58, was tall and hugely strong. He lived on the Marsden side of the moors, and was an experienced gamekeeper, like his father before him. William Uttley was known to be a tolerant man who often let poachers off.

Uttley was found lying in a gully known as ‘Ben Clough,’ at 9.30am. It seemed that his body had been thrown into the 5ft deep ditch.

A gunshot wound was behind his left ear. The cloth on the upper part of his coat was burnt, indicating again that he had been shot at close range.

Another shot was found on Uttley’s back. This was a different type of shot wound. It had been fired at a distance of nine yards. There was no sign of a struggle.

Uttley’s dog, ‘Ben’ was said to be watching over the body of his master. Later enquiries indicated that the gamekeeper came onto the moors at 2.30pm on Wednesday September 9. After that he was never seen alive again.

The second victim found was Robert Kenyon, aged 26. He was the son of James Kenyon, who was head gamekeeper.

Robert sometimes stayed with his father (James) at Buckstones house, overlooking the moors. He helped his father out when he could. This was ultimately to cost Robert his life.

Over two hours after William Henry Uttley’s body was found Robert’s body was located by mill workers. It was in a gully known as ‘Deep Clough.’

The two bodies were a mile apart. There was no way of telling who had been murdered first.

Robert’s body was hidden under an overhanging ledge at the side of a stream. It was partially covered with sods of earth, heavy stones and heather.

There was no sign of a struggle but his body had been dragged 30 yards to the burial site.

Robert had been shot in the head, from behind, at close range. The shot fired was the same type, used at close range, on William Uttley. Searchers would have missed the victim had Robert’s clogs not been showing. Clearly, the murderer or murderers were trying to hide the body.

So, what do we actually know about events leading up to the killings? Were there any witnesses? Certainly old Mr Kenyon appears to be one.

On Wednesday afternoon, September 9, he stated how he went out to range the moors with his son, Robert.

The Kenyons were standing on high ground. They saw a man on the moors walking towards them from the west, at Ben Clough/Cut, about three quarters of a mile from the main road.

Young Kenyon had given his father his shotgun, so he could run faster after the trespasser. Soon Robert was out of sight of his elderly father. Old Mr Kenyon never saw his son alive again.

James Kenyon claimed that he recognised the man as Henry Buckley (above), by the way he walked and by the way he carried his gun. He even claimed to recognise Buckley’s foot prints on the muddy tracks.

Mr Kenyon stayed on the moors until 6pm. When Robert failed to come home, he went out before darkness set in. He claimed to see a white face hiding in the moors, watching him.

Later again, at midnight, Mr Kenyon went to search for his son. He remained on the moors all the night. The old man must have passed within 50 yards of his son’s body.

Early the next day (Thursday) searchers went to the house of William Uttley to discover that there had been no sign of him from the day before – he had not come home on Wednesday.

It was clear something was very wrong and the moors would have to be searched in daylight. In mist and rain the dreadful discoveries were made.

The coroner’s inquest took place at Marsden’s Mechanics Hall on Monday September 14, and it caused a sensation. Up to 40 journalists were in attendance, such was the interest.

Mrs Uttley gave evidence dressed in funeral black. Immediately after the inquest, she went to nearby St Bartholomew’s Church. Here she joined a crowd of 7,000 people, such was the notoriety of the murders, for her husband’s funeral.

Dressed in his gamekeeper’s green jacket with brass buttons, knee breeches and gaiters, old Mr Kenyon took a piece of paper and wrote the name of the man he saw, with his son, on the moors.

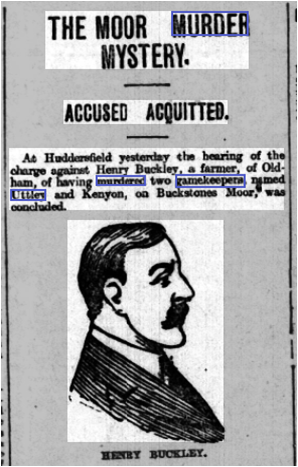

It was Henry Buckley, a dairy farmer from Sholver, in Oldham. The jury brought in a verdict of ‘wilful murder against some person or persons unknown.’ In 1918 Buckley committed suicide.

Local police were quick in arresting the chief suspect, Buckley. He was brought before the magistrates at Huddersfield on no less than eight occasions. Huge crowds gathered outside the West Riding County Police Court in Princess Street.

Although there was some circumstantial evidence against Buckley, his solicitor Mr G.P. Fripp of Oldham, argued that old Mr Kenyon held a grudge against his client, and that his story kept changing.

The eyewitness testimony of James Kenyon was taken apart by Buckley’s defence. They pointed out, old Kenyon was at least a mile away, from the poacher he saw on the moors.

The weather at the time was misty and raining and old Mr Kenyon would not be able to see clearly. To illustrate the point, Mr Kenyon was said to be unable to see if the poacher was wearing a hat or cap. It would be hard to convict anyone on this evidence.

Witnesses came forward to support Mr Buckley’s alibi. He had been on the moors, on the day of the shooting, but not where the gamekeepers were, at Buckstones.

There were plenty of reliable witnesses who saw Buckley leave the moors by 4.30pm on the day of the killings. The murders were believed to have taken place after this time.

Other witnesses attested to his good character as chairman of the Oldham Temperance Society and an active member of the Salvation Army. All this being said, he was known to poach on the moors.

Huge crowds gathered outside the Magistrates’ Court in Huddersfield and, at times, policemen on horses had to use their truncheons to maintain order.

Every detail of the court case against Buckley was covered by local newspapers. These ranged from old Mr Kenyon shaking his fists at the accused, to reports of shotgun cartridges and wadding, matching those found by Uttley’s body, being found at Buckley’s house.

At all times Buckley maintained his innocence and impressed onlookers with his quiet demeanour. On Friday October 16, the magistrates gave their verdict.

There was not enough evidence to justify committing Buckley for trial at Crown Court and he walked free to great celebrations in the courtroom.

Crowds at Huddersfield Railway Station waved him off as he headed home to Oldham.

Many felt that old Mr Kenyon’s primary aim throughout the court case was to find a man to hang for the murder of his son.

His evidence was not found to be credible. However, old Mr Kenyon swore until his dying day, that it was Buckley he saw on the moors. The police had to issue a restraining order to stop him from pestering Buckley at his home.

Public interest in the crime was tremendous, and thousands visited Buckstones moors. Guides at Saddleworth station met the trains and for a fee of one shilling conducted sightseers to where the bodies were found.

There is so much about these murders that remains uncertain. Was robbery the motive? William Uttley had five shillings in his pockets but it was not taken.

Robert Kenyon had a silver watch and chain, with a unique identity number, that went missing. Local papers said that if the watch was found on the person of someone, they would be the killer!

Five days after the murder, the watch and chain of young Kenyon was found in a red handkerchief, near the body of Uttley.

The weather had been appalling during the five days since the murders. Curiously, the handkerchief was nearly dry. Rumours spread that the nervous killer had returned the incriminating evidence. Did this point to the killer being local?

So, what did happen on that fateful Wednesday? Police felt that Robert Kenyon had been killed first, possibly by more than one man. It would have taken at least 15 minutes to conceal his body – most probably, in their opinion, while there was daylight.

William Uttley may have heard a shot and made his way to where it came from but nothing is certain. He did not have his gun with him on that day.

The murderer(s) possibly watched Uttley’s movements, while hiding in a gulley. He (they) then shot the gamekeeper from behind, as he passed. All of this is speculation!

The Huddersfield local press felt for many years, that a local man or men committed the killings, and that the local community knew of the killer or killers’ identity but kept silent. Those investigating the story felt that Henry Buckley knew more than he let on.

The inability to bring forward a conviction seemed to go against the forensic progress of policing at the time.

How could two men be murdered in the 20th century and get away with it? Had things not moved on in 50 years, when the double murders at the Moor Cock Inn went unsolved?

Inevitably, the police faced much criticism for their handling of the case, especially old Mr Superintendent Pickard, who was in charge of the case. He felt Buckley was the likely murderer.

It was the judgement of Mr Fripp, the defence solicitor of Buckley, that has led to much debate.

Fripp was of the opinion that the gamekeepers were victims of a targeted attack. He suggested poachers were more concerned in running away, rather than deliberate murder at close quarters.

Mr Fripp contended that William Uttley may have been murdered first, and Kenyon was then killed and buried.

Fripp felt it was the murderer’s hope that Robert Kenyon’s body would never be discovered, and he would be blamed for Uttley’s murder. Of course, the opinions of Buckley’s defence lawyer are, at best, clever speculation.

No one was ever charged with the murders of William Henry Uttley and Robert Kenyon, despite a sizeable reward of £300 being offered.

All the evidence has been laid before the reader to draw their own conclusions.

In truth Sherlock Holmes would be hard pressed to make sense of this baffling case. The culprit or culprits of these cruel and cowardly murders probably took their grim secret to the grave.

Read more intriguing features by Vincent Dorrington HERE