By Vincent Dorrington

Below Scammonden Dam embankment, hidden in woods, are the dilapidated ruins of Scammonden Cotton Spinning Mill.

In itself this is not strange. But this mill never operated – not even for one day. The story of this silent mill has become woven into local legend but controversy still abounds as to whether it failed due to incompetence or skulduggery.

In the 1850s Deanhead valley was a sour land with 400 or so people struggling to survive on their farmsteads. They had one advantage however – the soft but hard flowing water of the Black Brook.

Cotton manufacture, both weaving and spinning, had brought wealth to Lancashire. It was starting to do the same in some Yorkshire valleys, like the Ryburn. Locals, adventurous folk, of Deanhead and surrounding villages began to wonder if it could do the same for them.

Cotton and a cotton mill, employing a thousand people, would bring hope to the valley and stop the drift of local people to the mills of Huddersfield and Halifax.

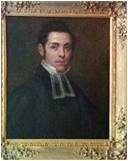

No one believed this more than the local doctor, John Kenworthy Walker, of Spring Grove. Soon a mania to build a cotton mill swept over the valley.

In April 1861 rules were drawn up and directors were appointed for the formation of the Scammonden Cotton Spinning Mill Ltd.

This was a mill that was going to belong to local people and not rich business speculators. The directors were full of confidence for the enterprise.

Shares were issued at £5 apiece, with a limit on 100 shares. However, at first only £1 down-payment was needed to secure the shares.

Many people bought four shares, a commitment of £20. This was, in effect, the entire life savings for the weavers, farmers and millwrights in the community.

Even before the foundation stone was laid 2,000 shares had been sold and registered capital for the enterprise was £30,000 – the same amount of money it cost to build Huddersfield Railway Station.

The project seemed set for certain success. Its committee pointed out that there was a 48ft waterfall from Deanhead Reservoir, which would supply power for a water wheel in all seasons.

Initial capital was used to purchase 26 acres of land, quarries with the finest white rock and 11 cottages.

Then in June 1861, 7,000 people attended the foundation stone being laid with a silver trowel by Dr Walker, whose brainchild the scheme was.

Miss Shaw of Barkisland sang to the expectant crowd, who were then called upon to buy more shares. Success seemed to be assured?

The shell of the mill was built with the finest white stone from the nearby quarries. It rose up and up to six storeys high, dominating the landscape.

Then a roof was put on the structure. The top level also had a floor put in but there were no doors or windows – the money had run out.

It was a huge mill, the biggest in the area, capable of housing 38,000 cotton spindles. Day trippers came from Huddersfield and Halifax to see the colossus. However, not a single machine was put in.

All this was happening when cotton mills were being closed down in the neighbouring Ryburn Valley. By 1865 money for investment had dried up and the project came to a stop.

In August 1865, the shareholders met at Pole Moor Baptist Chapel and decided to go into voluntary liquidation, a terrible blow to all the shareholders who had risked so much and lost everything.

Joseph Dyson, a local man of 67, had lost his investment of £150 and could not face the future. He took a lantern up to the top floor and threw himself off. Others are believed to have followed his desperate example.

By 1867 the mill was bought, by a mystery buyer at The Cock Inn in Halifax, for £4,000. The mill alone had cost £14,000 to build.

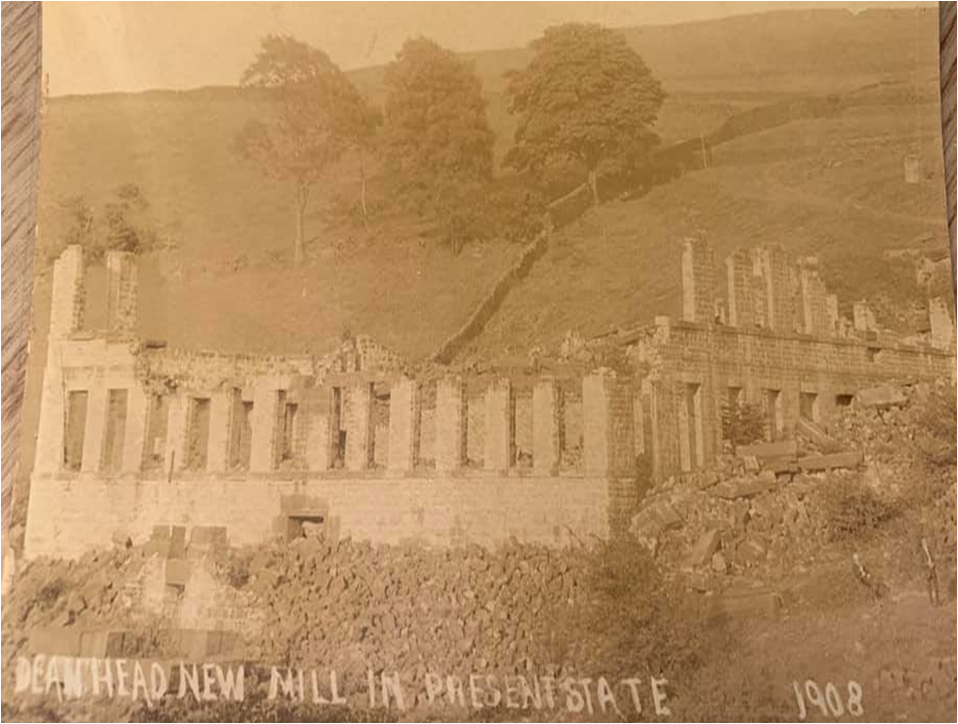

Local hopes that an investor would turn it into a textile mill proved to be forlorn. In 1897 a Bradford builder bought the mill for £250.

Sadly, he was only interested in selling the stone, so he demolished the mill. A wire rope, like the one used by the aerialist Blondin to cross Niagra Falls, was erected.

It ran from the mill to the Barkisland side of the valley, carrying huge stone blocks. Transporting them by road was impossible because of the lack of access. It is possible that the ‘no road’ legend started from here.

Local tradition lays the blame for the mill’s failure on the committee managers and their lack of foresight. It is claimed that no access road was secured to the mill – that a drover and local landowner simply refused to give permission for a road to be built across his land.

This ensured the total collapse of the project. No access road meant, in effect, no mill. The Halifax novelist, Phyllis Bentley, wrote her novel ‘No Road’ based on this premise.

Actually the committee did spend a considerable amount of money transforming a country track into an access road. It is marked on the liquidator’s estate plan of 1867 and the road still exists today, albeit in an overgrown state.

However, the more likely reason for the mill never opening was the shortage of cotton coming from America due to the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Cotton imports into this country fell by 50% in 1862 and only recovered by 1870. Big investors saw no point in throwing good money after bad.

The mill project did not collapse because the mill was in the wrong place or had no access road, but rather because it was built at the worst possible time.

Finally, another intriguing fact has added to the mystery of the mill’s failure. It appears that the Scammonden Cotton Spinning Mill Company had hopes that the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company would build a spur from the proposed Ripponden valley up the Scammonden valley, in the New Hey area.

This would have enabled spun cotton to be transported on the New Hey Road (A640) to the railway connection and then onto Manchester and other northern towns.

Unfortunately, by 1865 the railway proposal was rejected leaving the mill too isolated from its markets. Possibly this was the last straw that led to the liquidation?

The truth about the failure of Scammonden Cotton Mill may never be fully known. The desolate remains of it, beneath the embankment of Scammonden Dam, covered in trees and undergrowth, will not give up all its secrets.

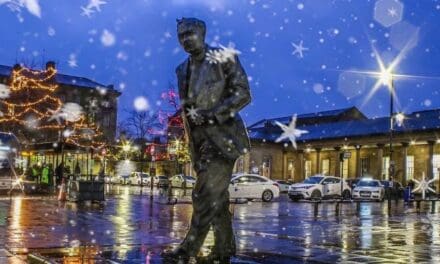

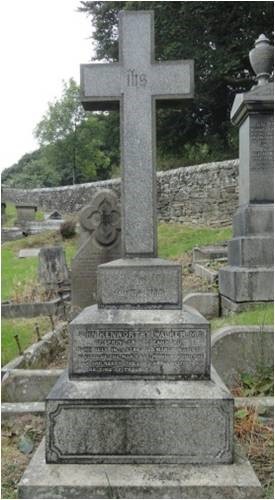

Barely a mile away in St Bartholomew’s churchyard, above the same dam, stands the grave of Dr John Kenworthy Walker, who first proposed building the great mill. Together they rest in peace, indelibly linked by history.