By Vincent Dorrington

From the coming of the Romans to the coming of the M62, the village of Outlane has endured an often troubled but fascinating history.

The story of this Pennine village, on the edge of the Colne Valley, gets little mention in history books and yet there is more to Outlane than meets the eye. What follows is the story of three great roads and their impact on Outlane.

The finds of local farmers led to an excavation taking place in a region of Outlane known as Slack in 1824. This and later excavations confirmed the existence of a Roman fort dating from 80 AD until 140 AD.

This was in part a cavalry fort holding up to 500 auxiliary soldiers. The men belonged to the IV Cohort of Breuci, who originated from the Balkans area.

The function of the fort was to guard the busy Chester to York road. A civilian community of local tribespeople known as the Brigantes built a settlement next to the Roman fort. This settlement was attached to the fort (vicus) and served the needs of the Romans.

It appears that this was the first civilian community of any size to exist, in what became known centuries later as Outlane.

Once the Romans left England to defend their Empire very little is known about the Slack/Outlane area.

Outlane, unlike Lindley and Quarmby, gets no mention in the Domesday Book. The region probably was no more than open moorland.

By the eleventh century it would have an abandoned and decaying old Roman road running through it. Some historians think that during the Dark Ages Saxon and Norse warriors marched along this old road as they tried to establish their local dominance.

The road which had brought life to the Slack area under the Romans, was now exposed to dangers beyond the settlement’s defences so it ceased to exist.

So where does the name Outlane come from? Its origin lies in the Old English meaning “a lane, leading away from a farm or hamlet or township.” The name suggests a community that was insular and removed from other villages.

For centuries Outlane has bordered the ancient townships of Longwood and Lindley and Stainland, so it is most likely that one of these townships gave Outlane its name.

Records make the first mention of Outleyn or Outlane in the 1530s when the area was populated by a scattered community of farmers and weavers. If this is the first mention it could well have existed some time before this.

Outlane as an area of importance hardly existed until the 1700s. Packhorse routes ran through it to Marsden. It is likely that the area was characterised by a few more scattered farmsteads with tracks and ancient routes that made their way into Lancashire.

One such route could have been along Lindley Moor Ridge, into Turley Cote Lane, down through Mulehouse Lane and into Outlane.

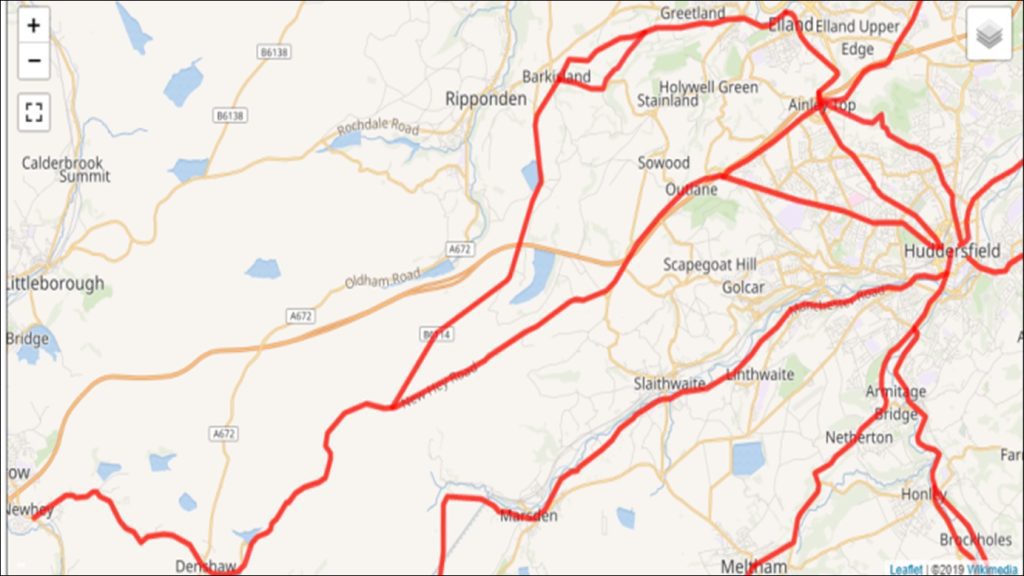

The building of the New Hey Turnpike Road in the early 1800s was the next major road to impact on Outlane – it literally put Outlane on the map.

Outlane now stood on one of the main routes from Lancashire to Yorkshire. This benefitted the village greatly as it developed on both sides of New Hey Road.

Perhaps Gosport Mills (built in the 1860s by the Sykes family) was the greatest beneficiary with the coming of New Hey Road.

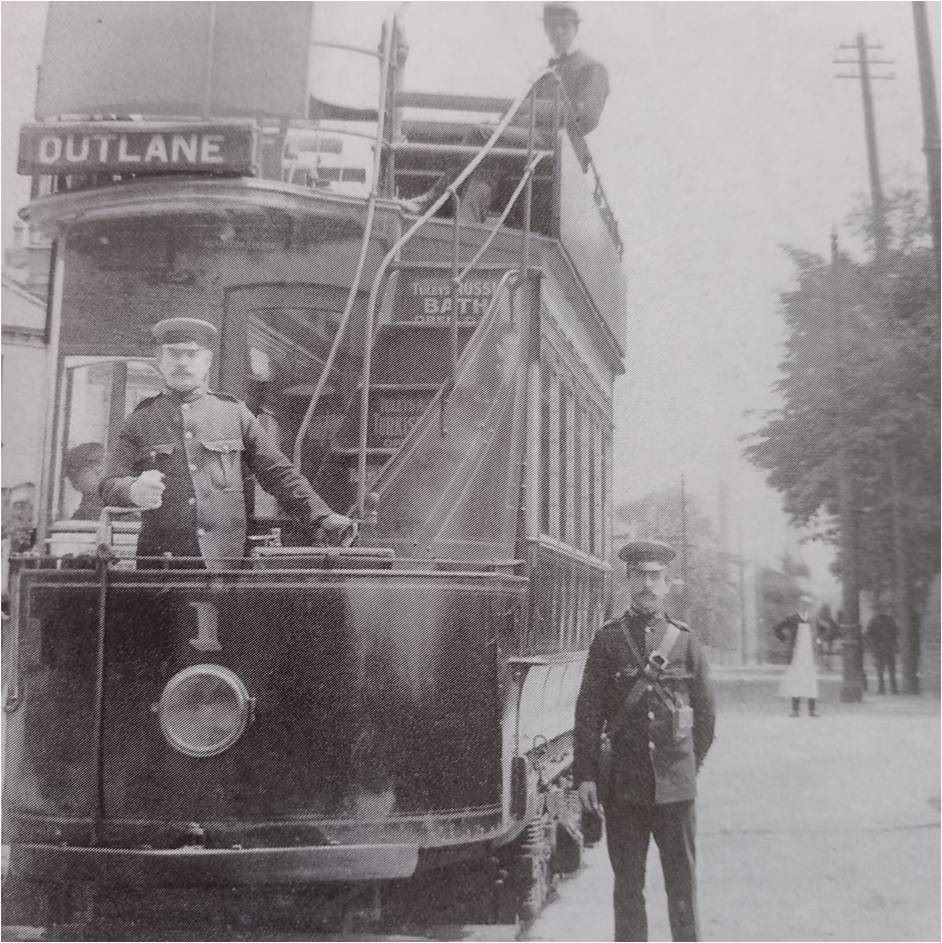

It became much easier to get its goods to market, even more so when the great road was opened up to trams in the early 1900s.

Engineering works like Stott’s now began to develop in Outlane to support its growing industrial and commercial needs.

The village became less isolated and began to create its own identity as it connected with Huddersfield more. Inns and public houses began to sprout up for travellers along the great turnpike road, that meandered through the moors. Hauliers like the Gees and Saxtons came into their own, especially as travellers flocked to the moors.

A chain of public houses stretched from the Lower George on the moors to the Swan in Outlane.

Many travellers came to escape the smog and smoke of Huddersfield and Halifax. Excursions to the Scammonden Valley, Scapegoat Hill and Buckstones with their panoramic views proved to be a real attraction.

Trams ran to Outlane from 1901 to 1934 and then trolley buses from 1934 to 1968, going as far as Outlane terminus. It was from here that local horses and carts of hauliers ferried visitors to the moors.

Over the generations there have been many distinguished families and individuals of Outlane connected with transport. John Thomas Gee, affectionately known as the ‘King of Outlane’, stands out.

He returned from WW1 as a war hero after suffering injuries at the Battle of the Somme. In the 1920s he opened Gee’s garage, at the foot of Leeches Hill with his brother Percy.

John Gee was a great innovator. Ever the opportunist Mr Gee took full advantage of living on New Hey Road.

His garage provided petrol for travellers on motor bikes, in cars, coaches and charabancs as they travelled to the moors. His garage was the first to have petrol pumps and later self-service petrol pumps in the Huddersfield area.

Gee’s haulage business became very successful. Bulk flour was taken to Elland and the haulage needs of all local mills especially Gosport Mills were met.

The Gee family had a long relationship with the Sykes family of Gosport Mill. They helped in its erection and many members of the family worked in the mill – at one time 10 of them worked together at the great mill.

The father of John Gee, a Mr Thomas Gee, looked after the horses of Gosport Mill and acted as coachman for Edward Sykes. The coach driver of Edward Sykes was killed at Crimble Clouch near Stainland in 1864.

John Gee was often called a force of nature and did everything in his power to serve Outlane. From 1940 he worked as a councillor and he served as Lord Mayor of Huddersfield from 1955 to 1956.

In 1964 he was awarded the MBE by the Duke of Edinburgh for his work with ex-servicemen, especially in supporting the disabled and looking after their pension rights. His wife Mary had energy to match her husband and served as Mayor of Huddersfield from 1965 to 1966.

When it came time to retire John Thomas made his son, Ronald Gee, general manager of G T Transport Ltd.

The aged but redoubtable John Gee lived with his wife Mary across the road from his garage. Their home was a red-bricked building called Alpha House. It is still in Outlane today facing the derelict Gee’s garage.

John Gee, like the rest of the villagers, would have been alarmed by the coming of the Big Road (M62).

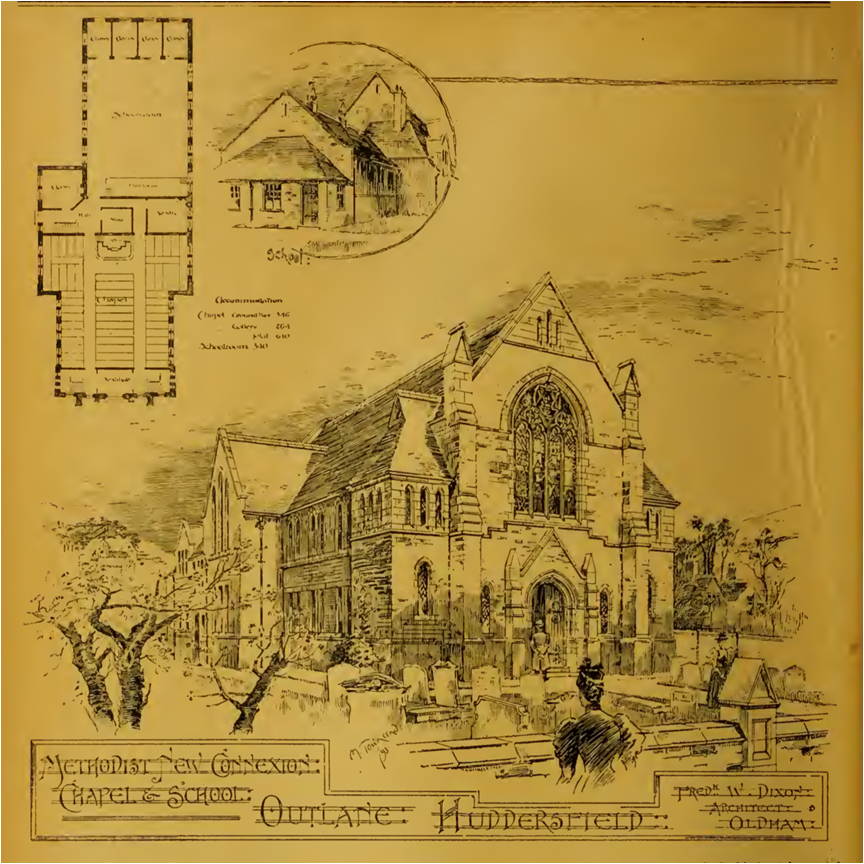

A public meeting was held at the Bethel Methodist Chapel in 1964 when villagers were shown plans of the proposed motorway. People started to leave after a question-and-answer session.

Suddenly there was a dramatic intervention. Market gardener Eddie Earnshaw jumped on the platform and asked people if they knew the scheme would kill the village. Only then did the penny drop. Mr Earnshaw was the hero of the day. Villagers decided to take action.

The original scheme would have taken the heart out of the village. A giant roundabout would have been put in the centre of the village, with on and off slip roads to the M62. This would have destroyed about 100 houses, as well as the post office and the clubhouse of Outlane Golf Club.

The bottom half of the village would have been cut off from the top half and Gee’s garage would have been in a virtual cul-de-sac.

At least the old Roman and Victorian roads had brought prosperity to Outlane. The new M62 threatened to bypass Outlane as if it didn’t exist and to leave it isolated.

Like an Ealing comedy the people of Outlane, led by Eddie Earnshaw, took on the Ministry of Transport by forming the Outlane Motorway Objection Committee.

For four years Eddie’s sketches of the likely destruction to the village were displayed at Gee’s garage. A public inquiry was held at Wakefield in 1965. The committee challenged the M62 architects and their barrister suggested an alternative route that would save the village.

The Minister of Transport turned this plan down but the objectors’ plans for a roundabout on the top of Leeches Hill, allowing only a westbound access onto the M62 and eastbound access from the M62 was accepted by 1968.

The village of Outlane was saved by the skin of its teeth but it had changed. There were winners and losers.

Outlane Golf Club remained intact. Its golf clubhouse moved to Slack with the Roman helmet emblem prevalent for all to see. Members could sit in its clubhouse, looking upon the grandeur of their golf course below Scapegoat Hill, with the M62 out of sight at their rear.

John Saxton’s haulage contractors used the motorway links to greatly expand their contracts. Even Eddie Earnshaw benefitted by starting up a caravan park for passing M62 travellers and holidaymakers.

The population of Outlane actually grew as more people took advantage of commuting on the Big Road to Leeds or Manchester, though some complained about the confused telephone numbers caused by the changes.

Gee’s garage was one of the great losers with the coming of the M62. The Hartshead service area and Salendine Nook petrol station took away much of its trade.

It stands today, at the bottom of Leeches Hill, closed and awaiting demolition. Its petrol pumps are gone but the old garage seems to linger on, like some great relic of Outlane’s past.

Gee’s garage had played a great part in saving Outlane from the worst that the M62 could do to the village. There are villagers who still remember when it stood for all that the village of Outlane once was – independent, vibrant and proud.

Vincent Dorrington, of Mount Community Group, is giving a talk – ‘The Illustrated History of Outlane’ on Wednesday August 23 (7.30pm) at Mount Methodist Church, Moorlands Road, Mount, HD3 3QU. Entry is £2 on the door.