By Local Historian Vincent Dorrington

Driving along the A629 Halifax Road to join the M62 is often a fraught experience in modern-day traffic.

Most drivers are hardly aware that they are driving through Birchencliffe as they approach Ainley Top roundabout and give it scant attention.

Ironically it was the building of this turnpike road in the 1820s that put Birchencliffe on the map. It changed from a quiet rural hamlet to being a distinctive area of economic and industrial importance.

An 1805 OS map shows Birchencliffe to be a hamlet of 50 or so cottages built on and by a rocky outlet.

Residents of the nearby township of Lindley could literally look down on their neighbours. Birchencliffe folk were known as Dunnockers because their hamlet had the appearance of a bird’s nest resting on the rocks of Birchencliffe.

However, during the 1800s, Birchencliffe began to lose some of its rural and isolated identity. Maps indicate that by the 1850s there was a thriving mining industry around the old Grimescar road.

Though most of the coal was near the surface there was scope for deeper mining at the Burn and Grimescar collieries. By the 1890s mining appears to be stopped due to the coalfields being exhausted.

Birchencliffe, like most hamlets by the 1800s, had scattered rows of cottages and some farmsteads where woollen cloth was made.

However, by the mid and late 1800s its cloth production was eclipsed by the mills of Lindley. The hamlet never had its own cloth mill, its manufacturing development went in a different direction.

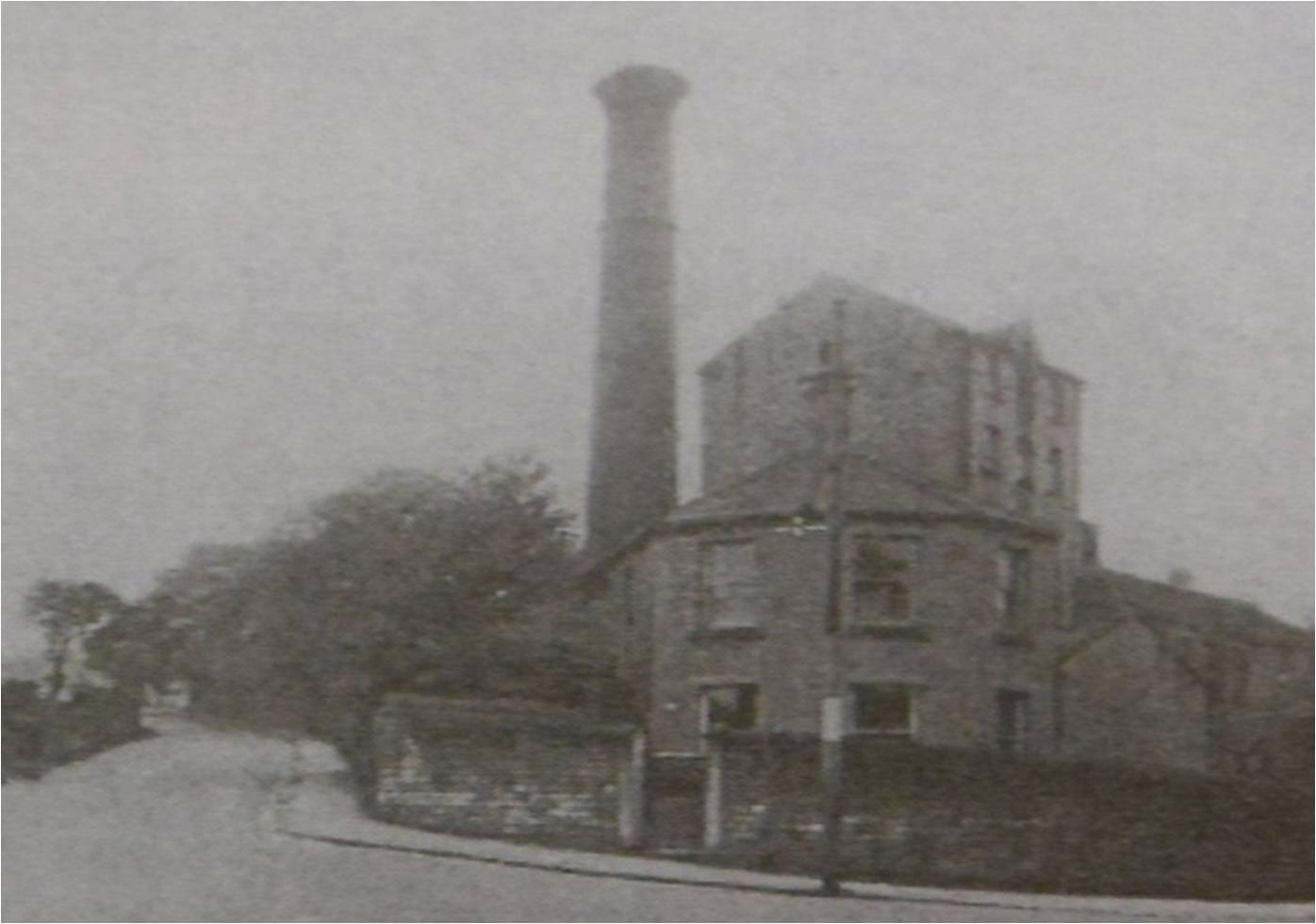

Royd Steam Brewery

By 1885 an OS map captures a vibrant and changing community. Dominating the skyline stood the chimney of Royd Steam Brewery and herein lies a compelling story.

It appears there was turf war between the breweries of ‘Bentley and Shaw Ltd’ of Lockwood and Benjamin Ainley’s brewery of Birchencliffe.

Things came to a head in 1927 when the Birchencliffe brewery and its 15 beer houses were incorporated into the Lockwood brewery’s franchise.

Beer was clearly important to Birchencliffe people. Not only did it have its own brewery, it also had four inns within half a mile along Halifax Road which were fought over by the great breweries.

These inns emerged in the middle of the 1800s but only one survives today, the Cavalry Arms. The others were the Boot and Shoe, the Royal Hotel (on the site of Da Sandro’s restaurant) and the Grey Horse (where Tesco Express is today). This was the last to close in 2010.

These inns and beer houses met the needs of passing trade in the late 1800s. Today, hotels like the Briar Court and Cedar Court, serve the needs of passing business people and travellers.

Perhaps one of the oddest features to do with beer and Birchencliffe is Combermere House. It survives today, almost hidden behind the Cavalry Arms.

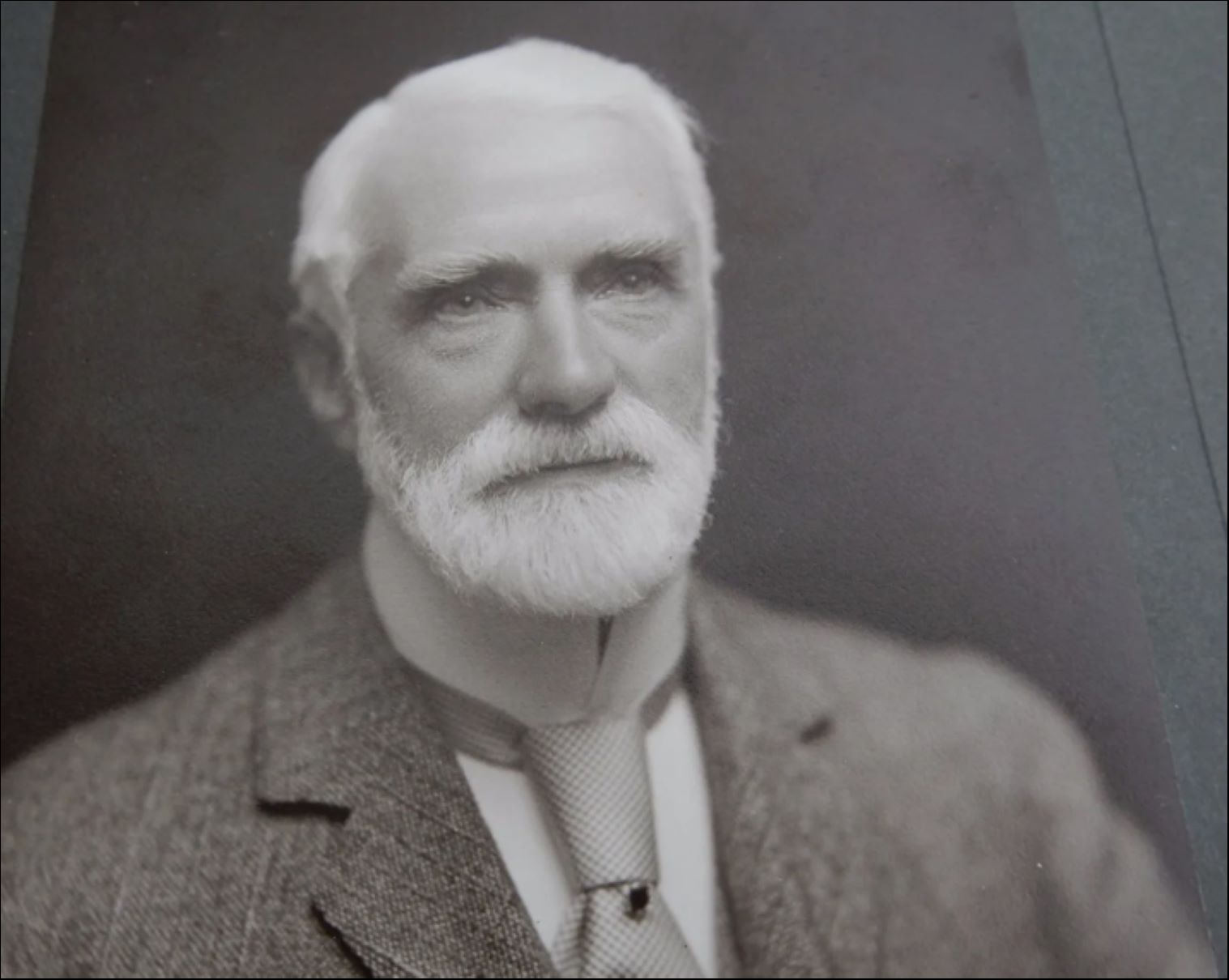

It was the home of Nathan Jagger, one-time managing director of Bentley and Shaw Ltd, the great rivals to the Royd Steam Brewery of Benjamin Ainley.

Nathan Jagger

Next to the great brewery on East Street stood another great industrial enterprise belonging to Birchencliffe – the Brick and Tile Works.

It came into existence before 1885 and was one of the largest local employers. Clay for the bricks came from nearby quarries like that behind Birchencliffe Hill Road, but mainly from the quarry on its site, actually next to the hamlet’s brick and tile works.

It is quite possible the brick works exploited the clay quarry at Blackley before Wilkinson’s Brick Works was built there in 1894.

During the 20th century, many of the homes of Huddersfield and Birchencliffe were made from its distinctive orange brick, before it closed in the 1950s. It certainly helped transform Birchencliffe into a suburban area where once green fields stood.

Most people think of the Garden Centre at Birchencliffe as being its most famous landmark. They would be possibly surprised to know that another great industrial landmark stood on its site until the 1940s and 1950s.

This was the chemical works that belonged to Ellis Barlow and was of a size that must have given work to many people in its locality.

By 1899 it went by the name of the United Indigo and Chemical Company Ltd or was part of its franchise – certainly Ellis was one of its directors.

The chemical plant was heavily involved with the use of indigo as a dye. Much of its exports went to the USA, especially New York, which needed the blue dye for the uniforms of its police, fire and army services.

When Ellis died prematurely in 1907 many hundreds of people attended his funeral at St Philip’s Church. Two generations later in 1944, his even more famous son, was buried in the same churchyard.

St Philip’s Church

Joseph Barlow was a Birchencliffe man of great renown and its most famed resident. He was the son of Ellis Barlow, who ran the chemical works in Birchencliffe Hill Road.

Joseph was a leading local Liberal councillor who rose to become the Mayor of Huddersfield in 1935 and 1936.

Locals remember him as the man who oversaw the destruction of Huddersfield’s old Cloth Hall which was replaced in 1936 by the Ritz cinema (one of the largest cinemas in the country).

Certainly, Joseph Barlow took an interest in the international stage of his time. He visited Germany in 1934 and warned people of Nazism’s menace long before it was widely acknowledged.

In 1936 he was one of the first mayors in England to offer Basque victims of the Spanish Civil War refugee status in Huddersfield. His commemorative monument in St Philip’s is one of the cemetery’s is most elaborate features.

Mayor Joseph Barlow

The brewery, brick works and chemical plant fitted in well with the modern manufacturing age of the late 1800s.

Yet there remained links with the hamlet’s agricultural past, none more-so than its old corn mill. It was built in 1900 and still ran until the 1980s under the skilful hands of William Sykes and his daughter Jennifer. Today, it stands next to St Philip’s Church as modern apartment blocks.

The distinctive religious buildings of Birchencliffe win the admiration of many people – clearly religion, as much as beer, was a key concern of people living in the hamlet.

As usual in this area of north Huddersfield, the Methodists were first to make their mark. In 1795 a Wesleyan Chapel was built in East Street – today it faces Lindley Infant and Junior School.

By 1868 the original chapel was converted into a Sunday School and next to it a larger Wesleyan Chapel was built.

Some nine years later, in 1877, St Philip’s Anglican Church was built on Halifax Road. It cost nearly £4,000 to build, and was a triumph for its first minister, the Rev Robert Wilford. He has been commemorated by having an eastern window of the church dedicated to him.

In 1963 the Church of Jesus Christ and the Latter Day Saints (Mormons) was the last of the great churches to be built in Birchencliffe at a cost of £180,000.

Not since the time of the Royd Steam Brewery chimney did a feature like the church steeple so dominate Birchencliffe’s skyline.

Tragedy then struck in 1992 when a fire destroyed the whole building. Today, another great white structure, belonging to the Mormons, stands on this site.

A fire in 2013 also burnt down St Philip’s Community Hall but it, too, has been replaced and stands to serve the community.

And what of busy Birchencliffe today? What would Joseph Barlow and previous Dunnockers make of it?

Little remains of the homes on the Rocks and even less of the hamlet’s manufacturing heritage. And yet it seems to be thriving with its shops and restaurants.

House prices in the area are rising steadily and apartment blocks have emerged in recent years. Of course, Birchencliffe’s location well suits the needs of commuters using the nearby M62 for work in Manchester or Leeds.

So, it would appear, that just as Halifax Road turnpike aided Birchencliffe’s growth and prosperity in the 1800s, the same could be said with the coming of the M62 – or the Big Road as locals called it in 1970.

READ MORE: Find more history features by Vincent Dorrington HERE