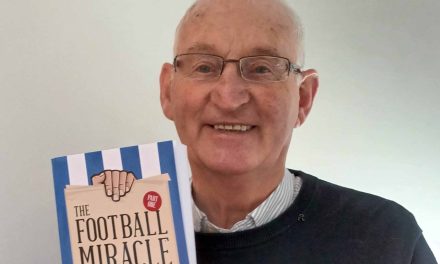

By Vincent Dorrington

Holywell Green is a quiet hamlet between Stainland and West Vale. Almost hidden away off the main road resides a quiet, almost forgotten park – Shaw Park.

Of all the parks in the Kirklees and Calderdale area this park is probably the most enigmatic, strange and even eccentric.

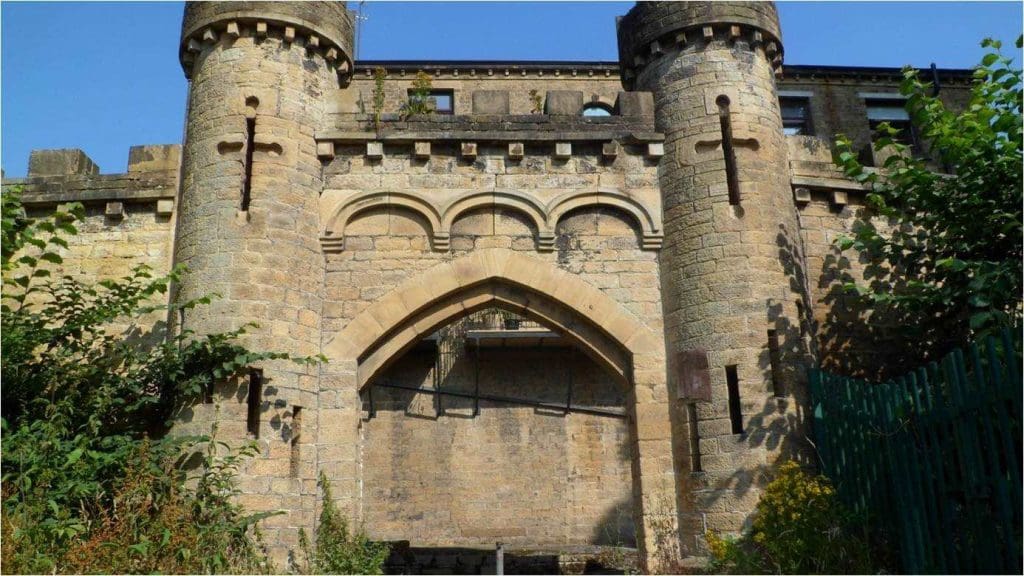

Many a visitor is at a loss when they first encounter its Arthurian towers and castle like walls. Then there are the grounds with their staircases that lead nowhere and plinths for statues that are missing.

The parkland is of an unusually ornate nature with its splendid pond – then there are the stone arches and aviary that seems at odds with these modern times. Clearly the past has left its mark and it is to this past that we must look to make sense of Shaw Park.

The Shaw family first came to Holywell Green in the 1790s when John Shaw built a carding and scribbling mill at Brook Mill at Holywell Brook. Finished cloth was taken to the Piece Hall in Halifax and before long the Shaw fortune and ambitions started to grow.

In 1806 a new mill was built called Brookroyd and two years later it was powered by the first of many steam engines. Profits rocketed during the Napoleonic Wars and even a Luddite visit of 1812 failed to hinder the profits of the Shaw family.

Victorian times saw the rise of the Shaws in becoming great mill owners and industrialists. Joseph Shaw succeeded his father John and, with his sons James and Samuel, made ‘John Shaw and Sons’ one of the largest and most important factories in Yorkshire.

By 1870 over 1,200 people were employed by the expanding mill complex, making it the largest ‘serge’ manufacturing mill in the world, stretching even to markets in China.

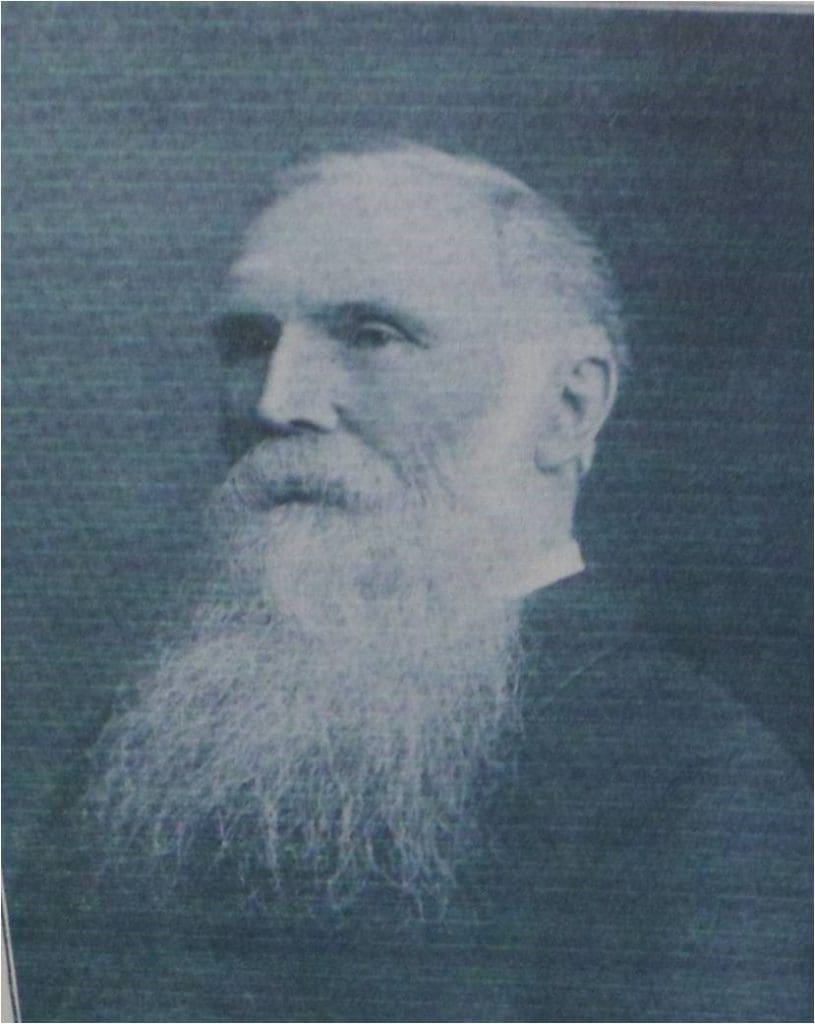

The driving force behind the great mill’s growth was Samuel Shaw. It appears that Samuel was a force of nature who got things done. He was a great benefactor to his workers. Shaw provided his workers with good wages and built solid homes like those around Honeymoon Square for newly-married employees.

He also financed the construction of the Mechanics Institute in Stainland – making sure that his employees were well trained and able to meet the challenges of a new technical age. Shaw was also concerned about the spiritual well being of his workers and financed the building of Holywell Green Congregational Church.

This great mill owner put Holywell Green on the map. As a ‘director’ of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company he proved to be a man of vision.

He was mainly responsible for the building of Holywell Green railway station in 1875. Brookroyd mills now became connected, through the rail network, to markets throughout the British Empire and the world.

John Shaw and Sons became a world force in the manufacture and selling of cloth. How Samuel Shaw had time to be a JP remains a mystery.

Shaw was a man of his times and desperate to show off the standing and status of his family. Between 1865 and 1868 he had an Italianate mansion called Brooklands built at the top of what is now Shaw Park.

It looked down on his huge mill complex that provided the profits for the great mansion to be built. A great tower rose from Brooklands mansion that became a local landmark.

It looked out over the main drive way and gatehouse in one direction. More importantly to Samuel it gave a great vantage point to look out on his gardens and great estate of over 150 acres. He could even see his stables which were made to look like a castle. Today it is the site of Castle Carr Hall.

There was much more than the house to see – there were other great structures. The lavish smoking house for guests stood on its own plot – Shaw hated the smoking habit.

Adjacent to It stood a huge conservatory. It was here that Samuel showed his horticultural skills. All species of flowers were grown and a hot house allowed bananas, bread fruit and vines to grow.

This great mansion even outshone nearby Holywell House, built by the Sykes of Gosport Mill in Outlane. In time these two great industrial dynasties intermarried.

Present day visitors coming to Shaw Park, who pull up in its small car park, are still greeted by Holywell House which has been turned into apartments.

Shaw was determined to develop the most lavish gardens in front of his mansion – gardens that would be more splendid than any other mill owners house in Yorkshire.

First, he had the five acres of grounds in front of his mansion landscaped with foot paths lined with great trees. Lavish steps led from his mansion (Brooklands) led to its grounds. Gardeners planted rhododendrons and laburnums throughout the estate. Swans, ducks and pheasants wandered around the parkland. Beehives were to be found throughout Samuel’s manicured lawns.

The imaginative use of water by the head gardener, Mr Pybus, was a notable feature of the gardens. Waters were diverted from Holywell Brook to feed a great pond and its fountain. This was just below Samuel Shaw’s mansion.

On the other side of the estate a decorative grotto was constructed with a dripping well inside it – this was fed by a local spring. Huddersfield and Halifax had never been seen anything like this before.

Undoubtedly, Samuel Shaw’s love of birds was the main reason for him developing his estate. A walled sanctuary for wild birds to nest was built from Shaw’s mansion – it was called ‘Castle Walk.’

It consisted of three mock towers connected by castle like walls. This gave the impression of huge castle that overshadowed the grounds. Rooms were inside the towers so Shaw and his guests could enjoy the views of his estate in the summer.

During the holidays of his youth Samuel had travelled to the Rhine Valley viewing its many medieval castles. This clearly had left an indelible impression on him as did his reading of Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe.

Samuel Shaw’s whole Arthurian sham castle site, including its dominant gatehouse, is a listed structure today.

His parkland contained the largest private aviary of its time in Britain. It was the Victorian fashion for wealthy men to keep collections of birds and to exhibit them to visitors.

This was made all the more possible with the building of nearby Holywell Green railway station. It seemed to have a dual purpose for Samuel Shaw – to access new markets for his cloth but also to act as a way of importing birds to his estate.

Rare and exotic birds from all over the world were now brought to Shaw’s parkland for display. The range of breeds were many. Pride of place went to the pheasants and small tropical birds who were highly prized for their brilliant plumage.

Not only did Mr Shaw use his parkland for this, he also bred rare birds and even had a museum room in his Brooklands mansion full of stuffed breeds. He may not have been ‘the Birdman of Alcatraz’, but he was certainly ‘the Birdman of Holywell Green.’

A photograph from 1879 survives with Samuel Shaw sitting by his pond in the midst of his gardens. He appears to be a picture of contentment in a make-believe world of his own making.

Shaw’s remarkable photograph album revealing his great house (Brooklands) and its gardens at their height and can still be seen at Calderdale Local Studies Library. In a real sense they have captured a moment in time the world of Samuel Shaw.

From the 1930s descendents of Samuel Shaw opened up the grounds to the work people of Brookroyd mills. A sports complex was built where they could play tennis, bowls and golf.

Allotments were allowed to be built at the front of Brookroyd mills. From 1939 even a mill pond was converted into a lido – an open-air swimming bath. The workers were allowed to walk in the grounds to promote their health, but the estate with its gardens had changed – the world of Samuel Shaw had gone.

All things come to pass. Brookland’s mansion was demolished in the early 1930s though remarkably remnants of its ashlar stonework can still be seen on the houses of Brooklands Avenue. A few decades later in the 1970’s Brookroyd’s mill of John Shaw and Sons was demolished.

And what of the grounds so beloved by Samuel Shaw? In the 1950s Samuel Shaw’s grounds were donated by Raymond Shaw (grandson of Samuel Shaw) to Elland District Council – later Calderdale Council became responsible for their upkeep.

Today the parkland is known as Shaw Park. Young families can enjoy its swings and duck pond – but what sense can visitors make of the turrets and towers of this castle like Victorian folly?

Then there are the architectural features found in the parkland that seem to make no sense: the stone aviary and arches and steps that lead nowhere.

It’s true that they all belong to another time. No longer can members of the Victorian elite be seen wondering among the tree lined paths of Shaw Park, admiring Samuel Shaw’s estate.

But late at night rooks, crows and other birds can still be seen in the park. They fly above the folly towers and walls looking for a place to roost – so in some sense the remnants of Samuel Shaw’s world still survives and his legacy continues to linger on.