By Vincent Dorrington

Many places in Huddersfield hold onto their Victorian heritage, but few more than Wellington Mills in Oakes.

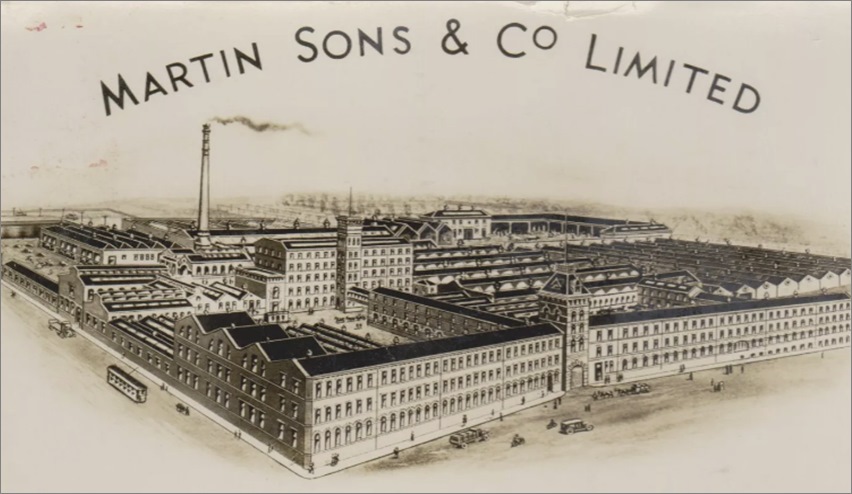

These massive mills have dominated the local landscape for over a century. In time these worsted mills became the largest cloth mills in Huddersfield.

Their emergence and triumph is mainly due to the perseverance and vision of one family – the Martins. This is their story.

Patrick Martin was born in Belfast in 1815 and came to Huddersfield in about 1840 finding work as a cloth designer.

Like many ambitious young men he sought out partners to manufacture cloth – in his own mill.

In 1864 Pat came to Oakes, taking advantage of George Walker’s financial misfortune. Mr Walker had fallen on hard times and was forced to auction his Lindley home and his five-storey mill at Oakes.

Pat Martin married his ambitions with his reading of the times – the manufacture of worsteds would make him rich.

Worsted manufacture first arrived in East Anglia from the Continent in the early 1700s. By the mid-1800s worsted cloth was mainly made in Yorkshire and hardly anywhere else.

Pat Martin’s plan was to quickly turn Wellington Mills from a wool mill (making woollen cords) into a hub of plain and fancy worsteds manufacture. In 1864 the mill had only 20 looms – in the next half century this was to grow to 600 and more.

Worsteds were made from smooth, thin but strong yarns with long fibres twisted around each other. It was particularly good at showing off its colours.

All agreed that it was the use of soft Yorkshire water, especially in the finishing process, that made Yorkshire worsteds the best woollen fabric that money could buy.

During Victorian times worsteds came into their own. Worsted suits and waistcoats, coats and shawls became all the rage.

Fancy worsteds or patterned worsteds held their colour. In time worsted furnishings could be found in most drawing and living rooms of the Victorian era and later.

It is interesting to note that Pat Martin was born in 1815. This was the year that the Duke of Wellington defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. In all probability he chose to name his mill to commemorate his birthday and the great battle.

Like most new enterprises Pat Martin’s venture had its ups and downs. With his partners he was able to borrow money from ‘The Huddersfield Banking Company,’ which had strong associations with the cloth manufacturing industry.

Then in 1867 calamity struck – a fire broke out in a teasing room where wool was being stored. At one time it looked like the whole mill would be destroyed but it was saved just in time.

Industrial agitation later showed itself when its workers adopted secondary picketing on behalf of other local mill workers who had their wages cut or rights restricted by their mill owners.

In 1914 mill workers held a rally, against management instructions, outside Martin’s entrance to protest against army conscription.

In the 1870s Pat Martin’s old partners left the business and his sons, Henry and Edwin joined the mill’s management.

Patrick Martin died in 1880 – that same year his youngest sons, Fred and John, also joined the firm. Messrs Martin and Sons Co was now run by four brothers – it had truly become a family business.

Developments then began apace. In 1880 another Martin’s mill was opened in Pellon Lane, Halifax. At its height it employed 300 people making worsteds.

In 1891 Henry Martin (eldest of the brothers) became chairman of the company and its main driving force. His uncle Edwin left the business in 1889 to retire in Norway.

Henry Martin was a chairman of ambition. Martin Sons & Co became a private limited trading company two years later in 1893.

The same year saw the total electrification of manufacturing at Wellington Mills. The company even had its own coal chutes at Hillhouse railway depot in Huddersfield.

By 1910 two coal trucks fitted with traction motors brought coal directly to Wellington Mills using the newly-opened tram lines on New Hey Road. It ran until 1933.

The early 1900s were probably the heyday of Wellington Mills when it was the largest employer in Huddersfield. It had over 600 looms and three huge mills on its site of four acres and more.

Martin Sons & Company had become fully mechanised and was able to cope with all aspects of cloth making from spinning to dying and from weaving to finishing. It employed over 1,700 workers in total and had offices in Huddersfield, London and New York.

The quality of its cloth was known all over the world. Henry Martin took pride in using only the finest yarns in his worsted production. It was said that one of his worsted suits lasted at least 25 years.

In 1912 it was visited by King George V and Queen Mary – Martin Sons & Co had really arrived! Its founder Patrick Martin would have been proud.

Sadly, his son Henry, the second generation visionary for Wellington Mills, died in 1910. It was his son Horace who enjoyed the proudest moment in the mill’s existence showing the King around his works.

Undoubtedly the Martins came to regard themselves as belonging to the Victorian elite. This was reflected by their homes.

Like all those who had built successful businesses in Huddersfield, they wanted to live in a fine house in Edgerton to reflect their status.

Edgerton was sometimes known as the mill-owners suburb of Huddersfield. Patrick lived at Ashleigh House on Halifax Road, but his son Henry came to live for 25 years at the finest villa in Edgerton. It was an ornate mansion called Stoneleigh.

Henry Martin came to employ nine servants including a butler, cook and maid. When he died in 1910 he left nearly £420,000 – making him a multi-millionaire in today’s values.

Later Ernest Martin lived at this residence. Horace Martin lived at Beechwood, in Byron Road Edgerton. The Martins had certainly come a long way.

Ernest Martin was one of the most colourful members of the Martin family. Son of Horace Martin, he took over the running of the mill in 1914. Three years later, in 1917, he was knighted becoming Sir Ernest Martin.

The company continued to thrive under his leadership, even during the Depression. Sir Ernest’s name was often found in the press.

In 1930 he was vociferous in arguing that Russian cloth imports to Britain and its Empire should pay higher tariffs to aid the British cloth industry.

Six years later he was in the newspapers for marrying a young Italian woman of 26 when he was in his 50s. At the proud age of 76 he was in the press again when his wife gave birth to a son in 1949!

During World War Two Wellington Mills continued to play its part making uniforms. However, it had a lucky escape when Luftwaffe incendiary bombs hit the mill in 1940.

Considerable damage was done to the weaving sheds. Fortunately, a bomb that landed in the mill pond failed to detonate and there was no loss of life.

After the war fire struck the mill again in 1951 threatening the whole mill. It started in the drying sheds and caused £10,000 worth of damage.

The mill and business survived until 1958 when it was on the verge of bankruptcy. It was sold with its patents and production rights to a rival consortium.

Sir Ernest Martin died the year before in 1957 knowing that the link between the mill and his family was going to be broken.

By 1976 Huddersfield Fine Worsteds were producing worsted cloth from Martin’s designs. Huddersfield Fine Worsteds became an internationally renowned fabric manufacturer, supplying the world’s biggest design houses and most prestigious tailors with superior and selectively-sourced fabrics. Even the Royal family was – and still is – classed among their clients.

What of Wellington Mills itself? In 1960 John Gladstone & Company (a Scottish firm of cloth finishers) moved into the mills. They diversified their weaving production.

Perhaps the demolition of the 175ft mill chimney in 1972 was a sign of things to come. In 1992 the company moved its production back to Scotland.

In 2003 Heritage Lofts bought the mill. By 2012 the mill had been named Heritage Exchange and was home to over 30 offices, a spa, health club, coffee house, as well as luxury studio apartments for over 50 residents and overnight accommodation suites.

Developers had sympathetically adapted features of the old mill, especially respecting its stonework and arched windows.

Today, residents and business organisations thrive together. Wellington Mills has adapted and evolved with the times – it has survived.

The same can be said about Martin Sons & Company’s worsted cloth (part of Huddersfield Fine Worsteds).

Both share a common legacy and owe their beginnings and success to Pat Martin, his family and the skill and hard work of generations of millworkers.